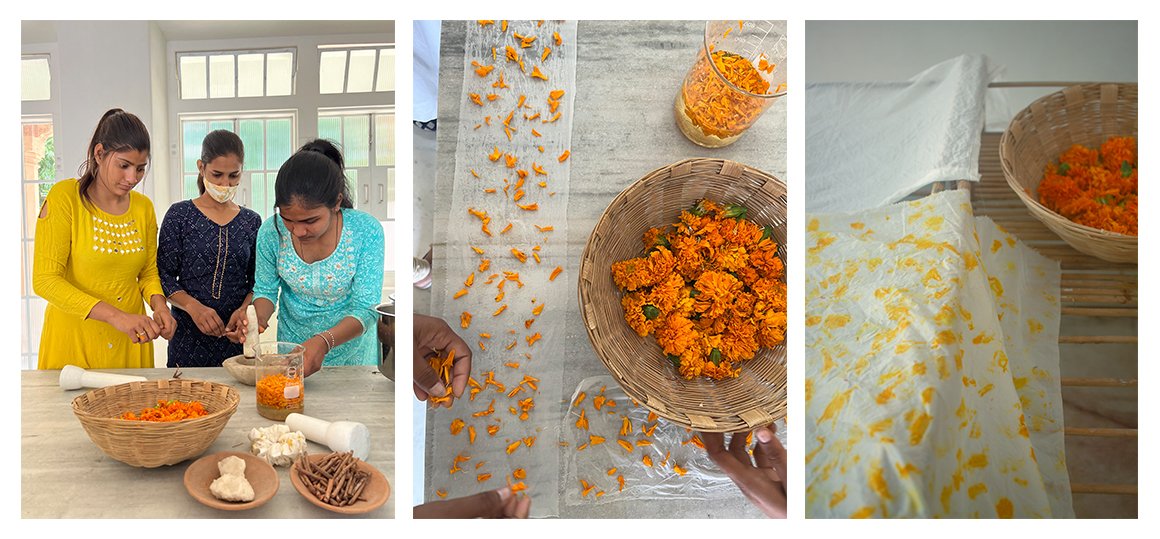

KITCHEN WASTE DYEING

with ONION and POMEGRANATE

08/10/2022

Before the 19th century and the synthesising of chemical pigments in laboratories, dyes for textiles were extracted from a range of natural ingredients like flowers, leaves, bark, seeds, minerals and yes - everyday raw food items.

Dyeing with organic kitchen waste has a double advantage of effectively minimising everyday household waste and bringing down the cost of natural dyes by recycling what we already have. With a few simple steps, common kitchen scraps like walnut hulls, pomegranate peels and onion skins can be put to good use to hide fading and stains on an old, well-loved t-shirt or experiments with tie-dye to create your own unique textiles for the home.

Because of how accessible it is, dyeing with kitchen waste is a wonderful introduction to working with natural dyes.

In a recent workshop at Nila House, we worked on dyeing with onion skins and pomegranate skins. Here, we share a quick note on the recipes along with the basic steps to keep in mind for your DIY dye experiments.

WHAT YOU WILL NEED

Dry onion skins and pomegranate skins: Collect your kitchen cast-offs and dry them daily for a week. If using onion skins, collect only the dry, papery outer skin. Any excess moisture will be a poor dye source and prone to mould. Ask your local fresh produce grocer to save you some peels!

Alum: This is easily available at a general store; the Hindi word for it is phitkari.

Textile blanks: Natural dyes work best when used with natural fibres, so all the more reason to avoid synthetic textiles.

Cotton thread if you would like to tie-dye.

Muslin cloth to strain the dye concoction.

Container to collect the dye-stuff; a 5L glass jar or beaker works well.

Pan to boil the dye bath.

Access to a gas stove or induction plate.

Access to running water.

THE DYE PROCESS

Preparing your fabric: Soaking and scouring.

Soak the fabric or garment in a mild soap solution for a few hours in room temperature water.

Rinse thoroughly to remove all the dirt and impurities in the fabric.

We recommend soaking the fabric overnight. The longer you leave your fabric/garment to soak, the more the fibres will open up allowing the dye to catch onto the fabric.

Prepare your mordanting solution by adding of alum to a 1 L of fresh water in a ratio of 8% of the weight of the fabric.

Soak the fabric in the mordanting solution for 30 minutes. The mordanting solution helps ensure colour-fastness. Pomegranate is rich in tannin and does not need extra mordanting.

Preparing the dye-bath.

Boil the peels in water, in a peels-to-water ratio of 1:10 , leave it on a simmer for 1.5 hours.

Strain the dye concoction using a muslin cloth as a sieve and collect the dye water in a wide-mouth vessel or pan for dyeing.

Dyeing

Heat the dye-bath a second time (add in more water in case it looks like it needs diluting) add gently add in the fabric

Stir the dye bath regularly to avoid patching

If you would like to make a tie-dye piece, use the cotton thread to create resists by tying knots in patterns across the fabric. This must be done before adding the fabric to the dye bath. Cotton thread is highly absorbent so you will need to tie multiple laters.

Watch out for steam burns. Use a long, light wooden stick to gently stir the fabric in the dye bath for 25-30 minutes.

Remove the fabric from the dye bath when you are satisfied with the colour; remember that natural dyes lighten so look for a colour a few shades darker than what you have aimed for.

Rinse the fabric under cold running water; remove the resists if you are working with tie-dye.

Set out to air dry in the shade.

RESULTS

Dyeing cotton fabric with generic purple onion peels should give you a colour ranging from green-ish yellow to a fresh, pale green and pomegranate skin should give you a beautiful, golden yellow.

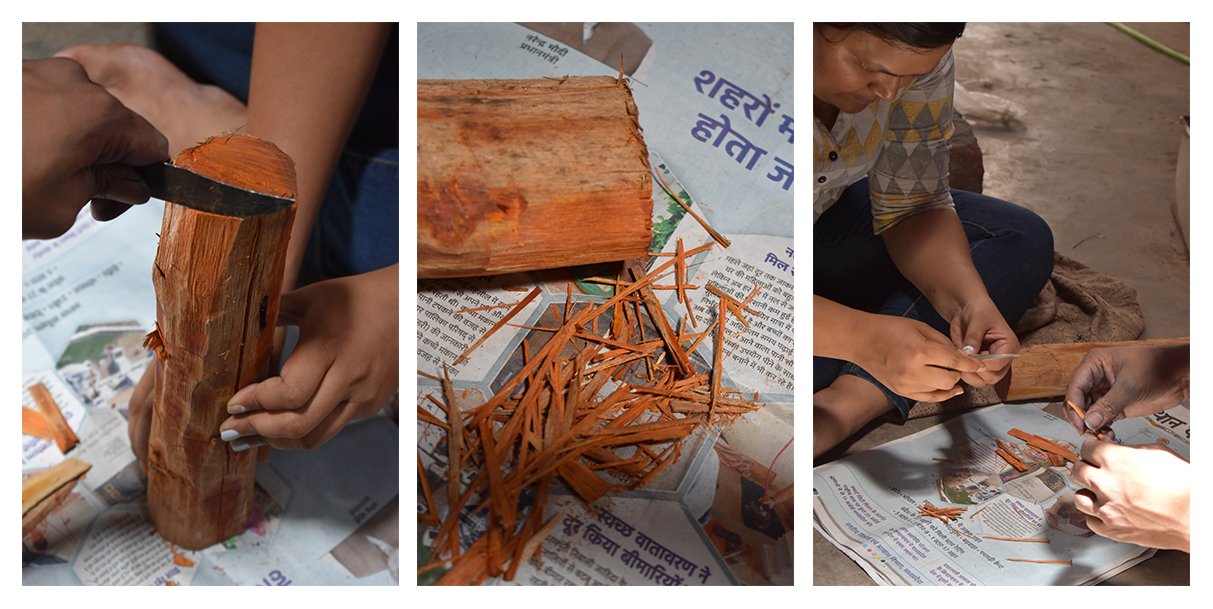

CRAFT STORIES: WOOD BLOCK CARVING

With insights from Rezwan Khan of Yaseen Wooden Block Carving

Sanganer, Rajasthan

20/09/2022

Block print textiles are the result of the combined skills of multiple artisan communities, created in a methodical, harmonious and slow process chain that has lasted for nearly 500 years in the Indian subcontinent. Whilst the skills of the printer (chippa) and the dyer (rangrez) are recognised in the making of a fine block print textile, it is also important to acknowledge the craftsmanship of the block maker -- story of this intricate textile craft begins in the open air workshop of the block carver. In India, wood blocks are still carved by hand using a simple wooden mallet and chisels of various gradations. Even small a buta block, no bigger than the size of a stamp, is a work of art.

Images: A Mughal block print, circa 17th century, from the Calico Museum collection, Ahmedabad; detail of a traditional block from the Nila House collection; a block carver in Bagru, Rajasthan; Saudagiri buti block, over 100 years old from Afzal Laduji’s collection, Ahmedabad; blocks arranged and archived at Dr. Ismail Khatri’s workshop in Ajrakhpur, Kutch

Over the years, we have been working closely with a second-generation workshop in Sanganer, Yaseen Wood Block. It is currently run by Rezwan Khan who oversees a team of senior and apprentice carvers. Sitting down in his pleasantly cool workshop front, surrounded by his archive of block designs (saved by date and category in binders) and carefully placed stacks of blocks, Rezwan shares that the story really begins with picking the right wood. Rezwan’s workshop prefers to work with sheesham or Indian Rosewood, though teak and pear wood can also be used. The wood must have no signs of damage or a crumbling grain, which would make it impossible to carve on; it is typically dried for at least 4-6 months to ensure there is no moisture. The wooden logs are cut into segments of typically 6-8 inches though it can go up to 21 inches as well.

Once the wood is selected, the process of making an average size block take about 10 days from start to finish. Before the carving can begin, the block face is prepared with a coating of chalk so the design can be traced or transferred on. Blocks are designed for either direct printing with pigments or resist printing. Blocks made for the latter require greater absorption for the resist to catch on and hence are designed to be deeper, with pores.

At the next stage the design is transferred onto the block face. This is an important and fascinating step, requiring immense precision. The design is first transferred onto tracing paper which is then fixed to the block face. The design is then meticulously marked onto the surface using a fine-tip metal pen called a ‘tipni’. The design once traced is checked thoroughly keeping in mind the spacing in between the motifs as well as the repeats. There are three main categories of Indian blocks – rekh or chief outline block; gadh or colour filler (the rekh design is carved intaglio ) and datta or background filler (typically carved in bold relief). A high quality textile can go up to seven colour ways. With three layers, this means 21 block could be used for a single textile.

Images (L-R): Blocks soaking in mustard oil at Nila House; tracing a design onto a block piece before carving; rekh, gadh and datta blocks with the corresponding printed textile from Brigitte Singh; a pair of dhabu blocks at Nila House.

The actual carving is the last stage, turning a plain wooden surface into a work of art. At a traditional workshop like Rezwan’s, a carver’s workstation is a simple set-up of a low desk; the carver sits on the floor, close to the desk which allows him to work closely with the block. In Rajasthan, block carving much like printing, still remains men’s work as the workshops are often at a distance from the home. A few family print workshops remain the exception.

Giving us insight into the synergy between the block carver and printer, Rezwan shares – “We know each printer’s haath – his preference, an carve the block accordingly; the repeats, the weight and the size of the handle.” This sensitivity underscores the sense of care and depth of relationships between these two groups of craft practitioners.

With a wooden mallet (pachar) in one hand and the chisel (kalam) in the other, the carver deftly works this way through the intricate design. It is work of great concentration -- the only sound in the workshop is the rhythmic sound of the mallet hitting the chisel.

Because of the high level of skill required, Rezwan insists on a thorough year-long training or apprenticeship for newcomers to his workshop. Diligent practice and close observation of the work by senior artisans helps them develop a steady hand and pick up the nuances of the craft.

At the very last stage, once the block is ready, it is left soaking in mustard oil for at least 2-3 days to open up the absorption capacity of the wood before being put to use on the printing table.

From the early day of our work, we recognised to the importance of championing wood block carving as an essential link when thinking about the future of textile in India. It is an integral part of the textile story and the value of this craft must be factored in to the final value of a handmade textile.

To celebrate the incredible artistry of wood-block making, we are developing a block library that carries a range of old blocks as well as some of the newer designs that we have developed with workshops like Yaseen Wood Block.

It is also worth sharing that whilst Sanganer and Bagru are well known for their block carving clusters, Farookhabad in Uttar Pradesh is well worth a visit for anyone looking to work with or research the contemporary realities of block carving communities today.

Wooden blocks designed by Nila, part of the growing archive and block library.

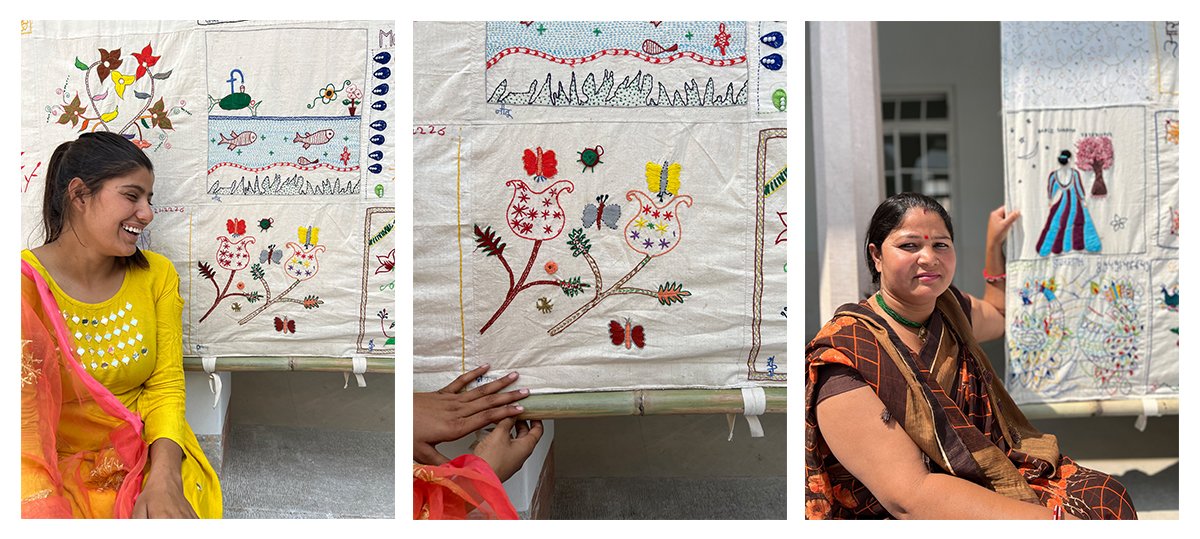

NILA SPOTLIGHT: PORGAI

A women’s collective reviving lambadi crafts in the Sittilingi Valley, Tamil Nadu

07/09/2022

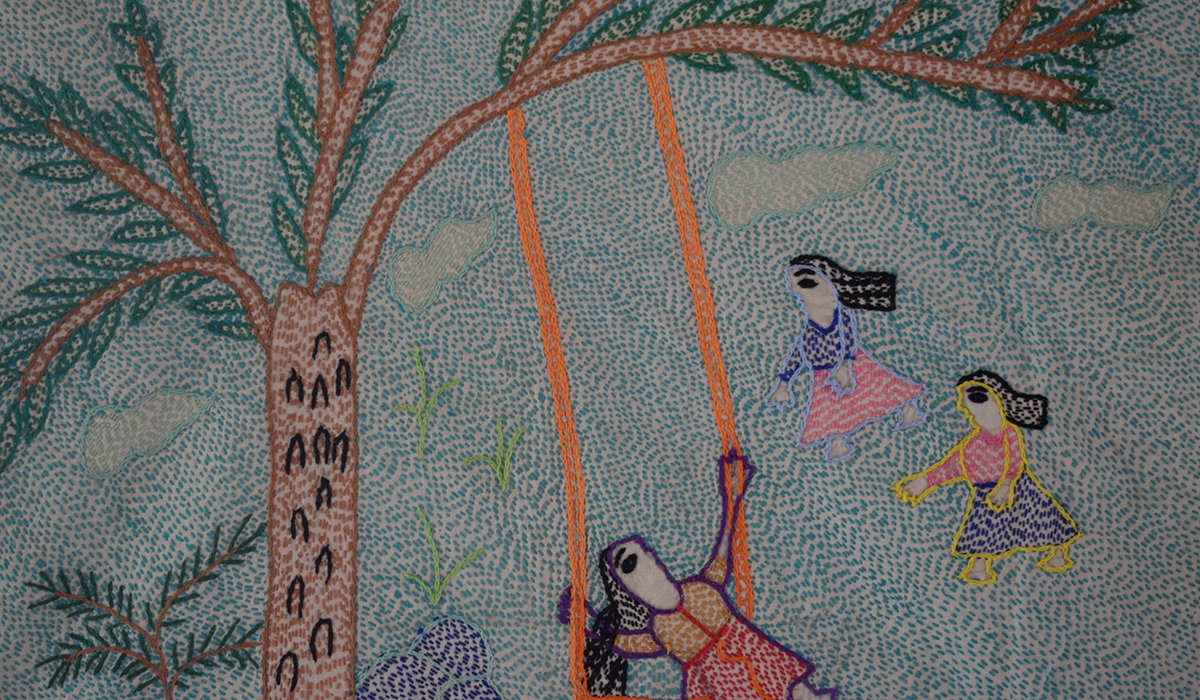

In August, Nila House opened an exhibition and sale of handmade textiles made by the women of Porgai - a craft collective started by lambadi women in the Sittilingi Valley, Tamil Nadu. Porgai translates from the lambadi dialect to mean pride. The story of Porgai is a moving example of a grounds-up, community-run initiative created by rural women to revive their heritage craft and reclaim their dignity through the strength of their community and traditions.

Here, we share Porgai’s story with a brief introduction and excerpts from our conversation with Dr. Lalitha Regi, who has spent decades working with the community and has facilitated the collective’s journey thus far.

You can know more about Porgai’s work through their website porai.org .

To place orders or explore collaborations, write to them at porgai@gmail.com.

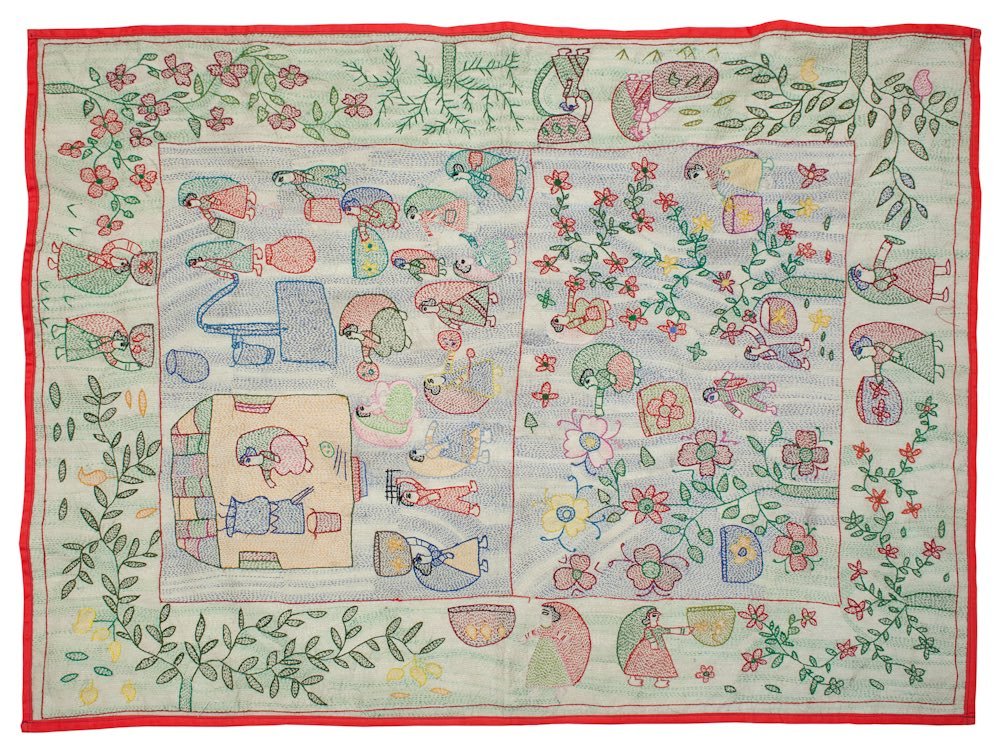

INTRODUCING PORGAI

The lambadi people are a nomadic trading community who migrated centuries ago from the deserts of Rajasthan, making their way across the forested western belt of India. The lush, hilly terrain of the Sittilingi Valley in Tamil Nadu, with abundant water and fertile land became home to one of the largest lambadi settlements. For centuries, the lambadi people have lived alongside other indigenous forest dweller communities in the hills of the Western Ghats, whilst remaining connected to their culture through traditions of dance, music and textiles. Lambadi textiles are richly embroidered works of art that would traditionally be worn by women everyday - a philosophy of quite literally carrying your wealth that is common among nomadic communities.

Life of the lambadi in the Sittilingi Valley. Images from the film ‘PORGAI (Pride)‘ by Anagha Unni

This vibrant textile culture, once worn with a sense of pride, has been on the brink of disappearing forever. Social stigma and pressures to blend into the mainstream has taken the younger generation away from learning the skills of making lambadi textiles.

In 2006, Dr. Lalitha Regi began an informal conversation with Neela and Gammi, two senior women from a lambadi ‘thanda’ (village settlement) in Sittilingi. Dr. Lalitha and her husband, Dr. Regi George have run health centres across the valley through their organisation Tribal Health Initiative since 1993. The connection between good healthcare and stable income was integral to THI’s work and speaking with the two senior women sowed the seed for Porgai as an enterprise that would revive the near-forgotten lambadi craft and help women create livelihood through the strength of their heritage craft.

Today, Porgai has 60 full-time members who create high quality, contemporary lambadi textiles that reach an international market through exhibitions and trade fairs. Most recently, their specially commissioned artwork for WIPRO, designed in collaboration with Anshu Arora Cheriyan, has been presented at the National Museum as a part of the exhibition ‘Sutr Santati’, presenting contemporary visions for Indian traditional textile crafts.

Images 1 and 2: Younger Porgai artisans picking up skills through training sessions

Image 3: Specially commissioned artwork created by Porgai in collaboration with designer Anshu Arora Cheriyan, currently on view as a part of the Sutr Santati exhibition

at the National Museum (New Delhi)

IN CONVERSATION WITH DR. LALITHA REGI

Nila Jaipur: Could you take us back to the start of Porgai’s journey? What were the circumstances that set the seed for Porgai?

Dr. Lalitha Regi: I met Neela and Gammi in 2006 while we were working to set up one of our auxiliary health centres in their “thanda”. In our conversation, the subject of lambadi textiles came up and they shared their dismay at the younger generation not engaging with their community’s age-old crafts. A lot of families had sold off their beautiful textiles in exchange for aluminium vessels. Neela and Gammi themselves had just a few embroidered panels left that had been saved carefully. Embroidery had not been practised in their community for almost three generations, though Neela and Gammi still remembered the skills they had learnt as young women. It was Neela and Gammi’s vision to revive lambadi embroidery that was the seed for Porgai. We spoke to the younger women, encouraging them to give a little time to learning the skills from Neela and Gammi. We also collected textile panels from lambadi settlements across Tamil Nadu to create an archive.

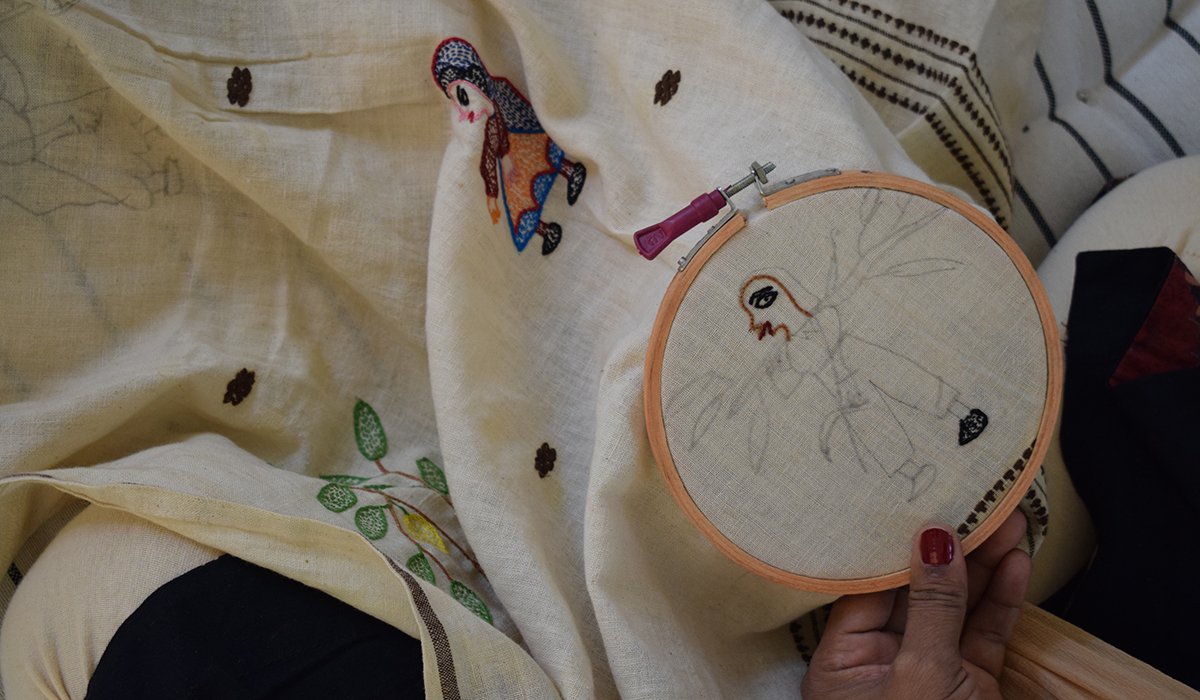

NJ: Could you give us a little insight on how the collective has grown? How did Porgai manage to create an interest among the younger women and what were the early training sessions like?

LR: From the start, the initiative was started and run by the women. The membership grew slowly, as others watched the Porgai members gain confidence in their skills and creativity. In the early days, the women were doubtful if anyone would care for their craft and purchase what they made. With every experience of positive feedback and building orders, their confidence grew. Working creatively and finding appreciation and recognition for this creative output is important for a sense of self-worth. In rural communities, women’s work is endless but goes entirely unrecognised. Porgai helps them quantify their labour, provide for their families and reclaim their vibrant of their heritage. We insist that every piece carries the name of the maker to add to her sense of worth and pride.

NJ: Could you tell us a little more about the impact of this craft revival initiative on the lives of Porgai’s members?

Over the years, we were witnessing a growing wave of migration to cities for work. This was bringing in livelihood but also bringing health and social problems. From our studies across several village settlements, we learnt that families would stay closer to their homes and communities if there were other avenues for earning. Craft allows them to get a sustained income but also tend to their land and look after their elderly because it’s flexible work - it can be done from home while organically multi-tasking, which the women do anyway! The income generated through their craft work has helped the women gain a more equal footing in the home.

The women of Porgai. Images courtesy Porgai.

NJ: What are some of the other support initiatives Porgai works on with its members?

LR: We work with small-scale farmers, part of the Sittilingi Organic Farmers’ Association, to source organic cotton and materials for natural dyeing. The organic cotton is hand-spun and handwoven in Gandhigram in Chinnalapatti (Tamil Nadu). Though the women’s work comes at the last stage of the chain (embroidery) the collective’s work is connected to every stage, with low carbon footprint processes and zero-waste goals.

NJ: The pieces made by Porgai are a wonderful combination of traditional stitches in more contemporary designs - how has this design innovation taken place?

LR: It has been an organic process, with a little design support from some of our friends such as the Bangalore-based designers Anshu Arora and Devika Krishnan to create exposure to new ways of looking at traditional stitches. We have also had design students from IICD (Jaipur) and Pearl Academy (Bangalore) work with us on capsules. But the ideas and setting the low imprint/zero-waste goals have come from the women. The designs, if you look carefully, are a pure response to our surroundings – the colours of edible seasonal berries; the varieties of millets and grains that sustain families; the lush landscape. The textiles are our way of thanking nature, coming full circle in terms of creative expression and the approach we follow.

Live craft demo at Nila House by Porgai, attended by students from the Indian Institute of Craft and Design (Jaipur).

NJ: How might those interested to work with Porgai reach out and support the work?

LR: We welcome collaborations with design studios and are open to individual orders or a reasonable value. The lead time for an order or commission is 2-3 months, depending on the size and details. Sittilingi is quite remotely located and we struggle with telephone connectivity, so it is best to reach out to us via email or through the form on our website. We usually respond within 24 hours.

Textile pieces by Porgai, as presented at Nila House. August 2022.

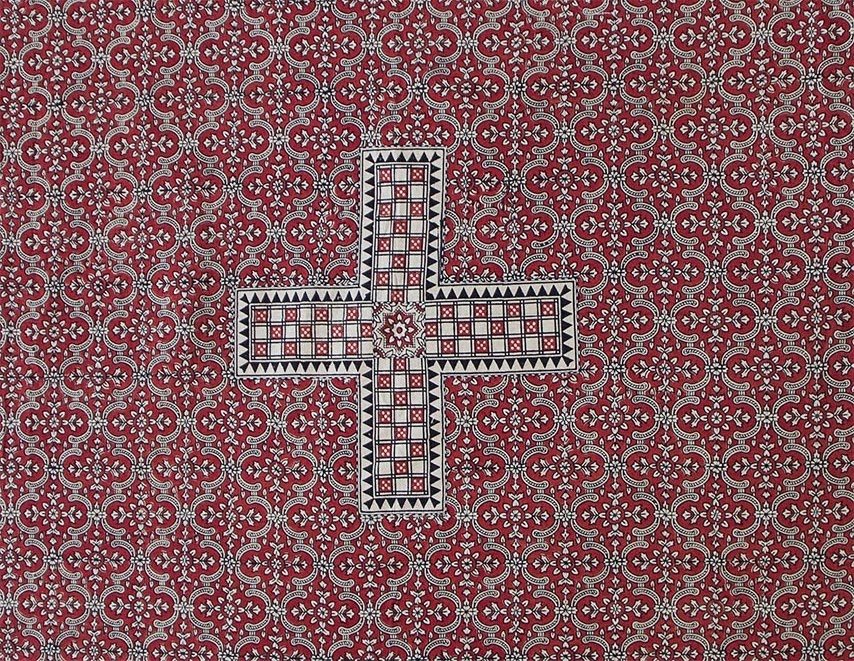

DHABU PRINTING: THE CRAFT OF MUD-RESIST PRINTING

10/08/2022

Dhabu is a technically precise type of mud-resist printing that gets its name from the Rajasthani word ‘Dhabao’ or ‘to press’. The earliest example of a dhabu textile dates back to 675 AD, with a specimen found in Central Asia. According to one local origin-myth, dhabu was discovered by accident when an indigo dyer – a ‘rangrez’ – dyed his dhoti in a vat only to discover that a spot of mud, caught accidentally on a visit to the riverbank, had stopped the indigo from catching on to the dhoti fabric. The beauty of his happy accident captured his imagination and dhabu mud-resist printing was born.

Dhabu belongs to family of hand-print textile crafts with process involving a resist to create a print resting within a negative space. In her research essay ‘Mapping Indian Textiles’ (pub. 2017, IGNCA, New Delhi), Ruchira Bose articulates the principles of print textiles – “Printing involves the placing or withholding of colour or pattern on cloth, thus producing two kinds of spaces: the embellished space and the background space, or, respectively, a positive space and a negative space. The distinction between the spaces defines where the cloth receives or resists the various interventions and this is the fundamental of hand printed techniques.”

With dhabu, a mud resist is created using a hand-carved wooden block. The mud resist is held in place to dry by mixing wheat chaff or saw dust that cakes on like a protective shell against the dye. Recipes for the mud resist paste vary from region to region, often guarded within the craft community as a precious secret. One of the most common recipes is a mix of local black clay (kali mitti), lime (chunna), wheat chaff (beedan) and natural gum (gondh). The mixture is boiled, then kneaded together by hand and left to sit overnight; water is added the next day and the mixtures is sieved, collected in the block tray to be used for printing. The resist printed textile is set out to air dry under the sun and once the resist firmly in place, the textile is ready to be dyed in a dye bath or vat. The resist is washed off with a thorough rinse at the end of the dye cycle. The complexity and value of a dhabu piece comes from the number of dye-dips and resist layers that are involved, creating a very special layered effect.

At Nila, our work with dhabu has particularly focused on reviving the use natural indigo. Like all printing and natural dye processes, dhabu is closely linked to the earth - both in terms of the materials that guide the process as well as what goes back the earth as a consequence of the process. The proliferation of quick and cheap synthetic dyes has serious ecological fall-out as the chemicals run into soil and water systems. Dhabu’s organic beauty and synergy with nature is completely offset by the use of these synthetic dyes.

Reviving the traditional around natural indigo dhabu printing has been possible in Bagru - a centuries-old rural craft cluster outside Jaipur - with the energetic support of local artisans, particularly Dheeraj Chippa. A seventh-generation printer, Dheeraj and his father, the master dyer and printer Babulal Chippa, joined our initiative to build a natural indigo vat for their community that would help create a local self-reliant, circular system. In February 2020, we collectively set up a 200L natural vat, increasing the capacity to 400L in the next few months. The vat continues to be looked after by Dheeraj and his family and utilised by the neighbourhood community of printers.

Dhabu is an example of why machine-made textiles can never hold a candle to handmade textiles, if we chose to look with sensitivity. It is also promising that young artisan-entrepreneurs like Dheeraj view working with traditional, slow crafts like natural indigo and dhabu as matter of pride. He shares - “I am motivated by the idea of create a piece that rivals a machine-made textile and shows off the value and depth of traditional, nature-based techniques. I chose to work in a high-quality, small-batch process and there are enough people all over the world who appreciate this.”

And whilst this is a centuries-old craft, there are still micro-innovations happening all the time, such as the hybrid screen-dhabu print technique we recently learnt of from master printer Damodar Nama’s artisanal studio Chaubundi. Innovation and craft preservation can indeed go hand-in-hand.

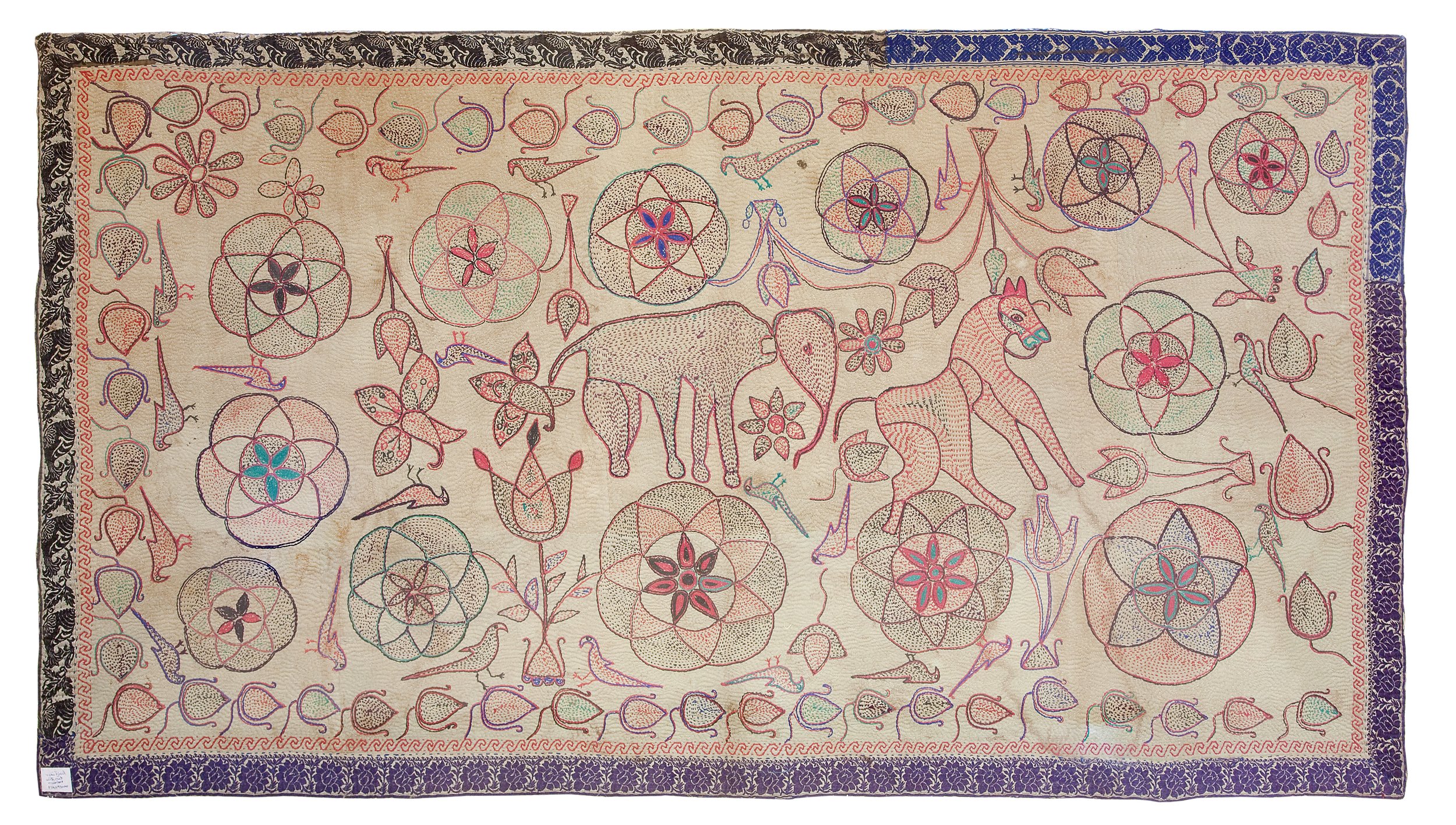

SUJANI OF BIHAR

In-conversation with SANJU DEVI, founder of Sujanimahila Jeevan Foundation

25/07/2022

Sujani / Textile of India / Craft Revival / Empowering Women

“Sujani” comes from the Sanskrit roots words su which means ‘to support’ and jani meaning ‘birth’. For hundreds of years, sujani textiles in the region of Bihar were quilts and swaddle cloths made for young mothers using old, well-loved textiles. An old sari or dhoti – soft with use – would be folded multiple times like a quilt and embroidered over, often using threads from the original textile. Traditional sujani motifs included auspicious symbols associated with the natural world and vignettes from folklore.

By the 19th century, this private craft of thrift and care was endangered as a result of the combined effects of industrialisation and colonisation. However, like its cousin kantha from West Bengal, sujani saw a revival in the early decades of the 20th century, encouraged by the cultural currents of the Indian independence movement.

Today, sujani is an important link in the social and economic lives of women in Bihar. The iconography of the embroidery has evolved to depict contemporary subjects like women’s rights and environment conservation. Through the inspired work of organisations like the Sujanimahila Jeevan Foundation, Bihar’s sujani has been recognised with a Geographical Indicator (GI) tag and has grown to become an art form for public consumption with a growing market all over the world.

To get deeper insight on the impact of sujani revival on the lives of women in Bihar and future visions for the craft, we spoke to Sanju Devi, the founder of the Sujanimahila Jeevan – an initiative that has grown from an informal Self Help Group (SHG) in rural Bihar to a 400-member strong registered foundation.

(You can support the SUJANIMAHILA JEEVAN FOUNDATION through direct orders via their Facebook: @sujanimahilajeevan and Instagram: @sujanimahilajeevan channels.)

Excerpts from our conversation with Sanju Devi.

NILA JAIPUR (NJ): What is your earliest memory of sujani?

SANJU DEVI (SD): Where I come from in Bihar, sujani was a part of women’s lives. As a child, I would sit by my mother and watch her hands work away on a piece of cloth – her hands were always busy, never idle. At an early age I also realised that working in this way was important to her.

NJ: What inspired you to set up Sujanimahila Jeevan Foundation?

SD: I got married at 13 and found myself in the new environment of the husband’s family. After having children at a young age, I began thinking of ways in which I could express myself creatively. Around this time, I met Viji Srinivasan and Dr. Sky Morris whose organisation Mahila Vikas (Women’s Development) was encouraging women to pick up sujani again as a way of staying engaged and coming together.

In our village (in the Muzaffarpur district of northern Bihar), we have a lot of ponds and fishing is a big occupation for the men, along with agriculture work. The women are left behind at home looking after the children and with very little time or purpose for themselves. Mahila Jeevan began having conversations with groups of women like me to encourage us to take up something that we could call our own.

With encouragement from Viji Srinivasan and Dr. Morris, I set up Sujanimahila Jeevan as an SHG in 2005. I took the lead with immersing myself in sujani, slowly encouraging a small group of women to join me.

NJ: How did you develop the market support for sujani?

SD: An introduction to Laila Tyabji played a very important role – through her, I was introduced to Dastkar and their huge network of customers in all the big cities. We began to take our work to exhibitions all over India, sharing our story. People began to take an interest in what we were presenting.

I was so happy when we won an awards for craft excellence from UNESCO in 2006 as well as a Geographical Indicator (GI) tag by India’s Craft Council.

I have also been developing our team’s skills with using Facebook and WhatsApp which have been very helpful tools to manage orders and staying in touch with customers.

NJ: What has the impact of the craft been on the lives of the women who are a part of SMJF?

SD: Sujani has given us a sense of pride in our history and in our own abilities. It is an incredible feeling to have people from all over the world take an interest in things we have made with our own hands.

NJ: What challenges did you face during Covid months and how did you overcome these challenges?

SD: The Covid months were very difficult as all our orders dried up and we had no opportunity to travel anywhere to bring in new orders. Our organisation’s carefully collected savings were completely depleted as we tried to support our members in severe need. But things are slowly looking up now, though we are still careful about travel – we cannot afford to bring the corona virus to our villages. Our visit to Jaipur, to Nila House, is our first trip in two years!

NJ: What is the future you wish for your members at SMJF?

SD: We are over 400 members at the moment and I hope to continue growing our organisation to reach every woman so she does have to stay unemployed and find strength for herself and her family through her sujani work. I hope to be able to take sujani to the rest of the world.

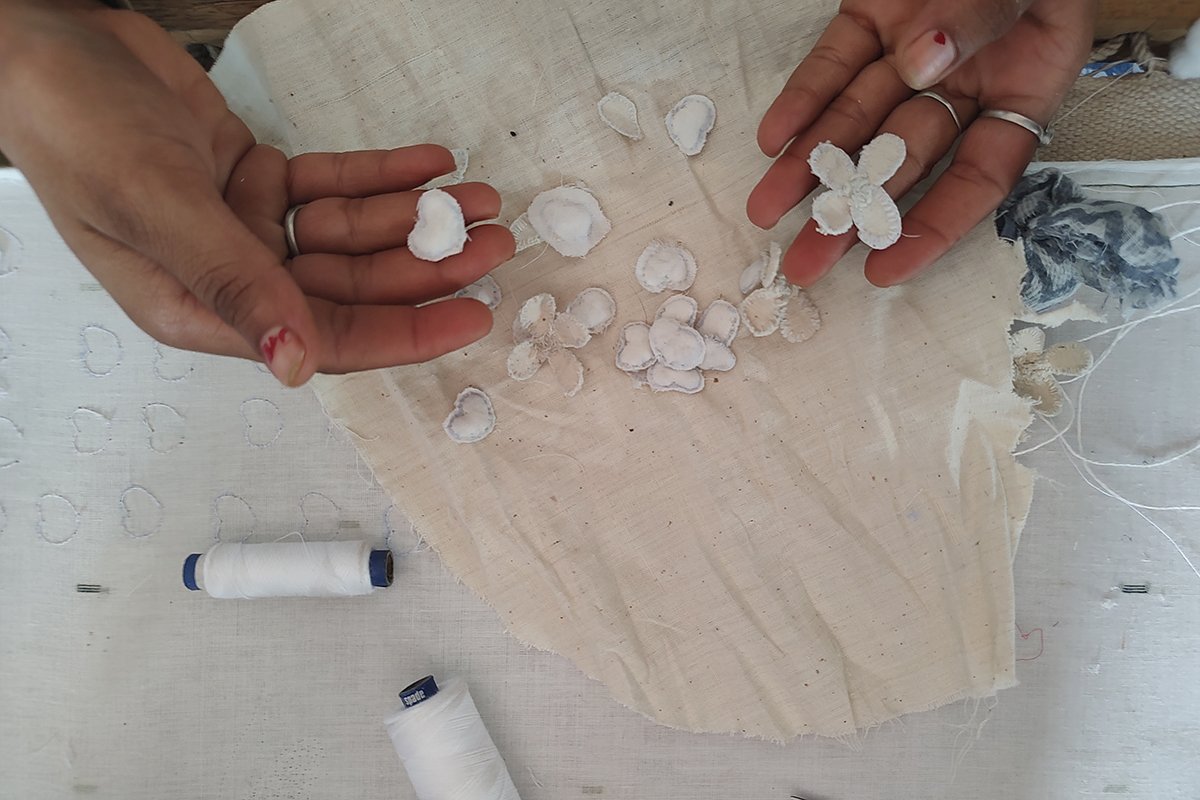

ECO-PRINTING: SPONTANEOUS, NATURAL AND SUSTAINABLE

20.07.2022

Eco-printing is the technique of transferring the imprint of plant material onto textiles using simple process of bundling, binding and heat from steam. Flowers and leaves are more commonly used, though natural detritus like tree bark and roots can also be used, giving beautiful results. The lightness of this process with its minimal material requirements and inherently sustainable, repurposing, all-natural qualities appealed to us from the very start of Nila’s journey. Over the last few years, we have been able to develop our experience with this process, exploring design possibilities as well as its potential as a regenerative craft that brings value to communities as a source of reliable, sustainable income.

OUR EXPERIMENTS WITH ECO-PRINTING

Nila’s first exploration of viable models to build an eco-printing practice began with a visit to Adiv Pure Nature’s set-up in Mumbai. A women-run enterprise founded by Rupa Trivedi, the clarity of their sustainability vision particularly resonated with us, particularly initiatives like their Temple Dye Project to collect floral offerings from temples to dye and print with for their ‘Temple Blessings’ textile collections. Working with the Adiv team, we developed a textile accessories using eco-printing with marigold.

We also worked with Aranya Naturals in Munnar, Kerala, using eco-printing with eucalyptus leaves in our exploration of healing plants. Eco-printing with locally abundant medicinal plants like eucalyptus transfers the healing aspects of the plant, creating a particularly soothing piece of sustainable design, particularly when working with hand-spun, handwoven textiles.

ECO-PRINTING AND COMMUNITY IMPACT

Eco-printing has emerged as a significant craft in our work around community training and skills-building. We have found eco-printing to be a wonderful way to engage women in rural areas who may not be proficient in specific skills such as embroidery or tailoring but can still engage with a craft that is seeing a growing demand among customers consciously seeking natural, sustainable textiles. Cost effective and easy to replicate at home, eco-printing is a forgiving craft that does not require tremendous technical expertise and allows free creative expression.

Through our training modules with women-led non-profit organisations like Saheli, PANS and our sister organisation, Lady Bamford Charitable Trust (LBCT), we have taken eco-printing to numerous groups of women in rural Rajasthan. Working with easily available local flowers, they have been able to master eco-printing techniques and present their naturally printed fabrics as a serious offering to customers and clients.

As we discovered through our own studio sampling and multiple workshops, eco-printing is a beautiful and easy introduction to sustainable textiles and dye crafts. Here, we have shared a step-wise guide to eco-printing that can be done in your studio or kitchen, using accessible, everyday materials. This gentle craft is also a wonderful activity for children.

WHAT YOU WILL NEED:

Foraged flowers – flowers from your garden floor or an old bouquet you might otherwise discard

Fabric to print on – this can be fabric blanks waiting to be dyed; an old t-shirt or plain cushion cover, ready for a second life

Cotton thread for binding

A vegetable or rice steamer and kitchen tongs

Alum for mordanting your cloth to ensure colour fastness

THE PROCESS:

Wash your fabric with a mild soap or cleansing agent

Create a mordant solution using easily available alum

Soak your fabric for an hour in the mordant solution, created by mixing the alum in water

(the alum should be 8% of the volume of the fabric)

Lay out your foraged flowers whole or as petals in an arrangement of your choice across the surface of the washed and mordanted fabric

Roll or fold the fabric, binding it in place with thread

Place your fabric rolls in the steamer; steam cotton fabric for 40-45 minutes; 20-25 minutes for silk

Take the fabric out of the steamer (use kitchen tongs to avoid steam burns) and let it cool

Remove the thread ties, unroll your fabric and soak in the mordant solution for 20 minutes

Rinse under cold water to remove the excess flower fragments and dry in the shade

GROWING CRAFT FUTURES IN RAMSAR PALAWALA

Nila’s journey with the women of PANS, Rajasthan

16.07.2022

Community Stories / Skills Building / Craft Training / Knowledge Systems

Time and again, we have seen craft being an invaluable source of empowerment for women, particularly in rural areas. In India, building sustainability around women’s livelihood security is particularly important as this has direct implications on the metrics of a community’s well-being – healthy and happy mothers and daughters reflect a most just, equitable society.

Creating livelihood opportunities for women through craft is one of our founding objectives. In our two-year journey at NILA so far, we have been fortunate to join hands with grassroot initiatives providing meaningful connections to communities. Working with these communities, we have been able to share our craft and design knowledge to support skills-building aimed to expand livelihood opportunities.

Our recent collaboration is with the People’s Awareness Network Society (PANS), a non-profit initiative working for two decades with groups of marginalized women and young adults in villages like Palawala near Jaipur. PANS’s sensitively developed model of holistic skills-building -- computer training along with tailoring; leadership-building along with healthcare awareness – resonated with us. With previous experience working with our sister organization LBCT, our studio and community-facilitation teams developed skills-building training modules that would create long-term security and additional income opportunities for families who depend on the land in this drought-prone region.

The first stage of our association was a session workshopping zero-waste ideas at Nila House in October 2021. The session was attended by 50 women across age groups and experience levels, who had already organized into a Self-Help Group (SHG). SHGs are community-based groups that come together as informal peer-run support groups. These groups are important because they establish the foundation of the community network, making it easier to access and benefit from the support of initiatives like our project with PANS.

As our relationship with the women at PANS Ramsar Palawala grew, so did our sense of their skills and aspirations. We invited a group of young embroiderers to contribute hand-embroidered textile artworks for ‘Stories of Healing in Cloth’, our public art installations with the Corona Quilt Project. Responding to themes of ‘Nature’ and ‘Rhythm’, 40 young women shared their dreams, goals and diligently developed skills through 15x15 inch embroidered pieces that made up one of the three key pieces in the exhibitions. It was a special moment to witness their joy and pride at seeing their artwork contributions presented in a public forum, celebrated by people from all over the world.

The next phase on our journey with PANS is creating a network of master artisans through intensive training sessions on embroidery, stitching and macrame. The goal is to create expert artisans who will be able to further train new artisans, thereby creating a system of skills-building and knowledge sharing within the community. Our studio has been working with smaller groups of women to introduce eco-printing and natural dyeing, pattern cutting, ari embroidery and macrame. We have already begun sampling pieces for future Nila collections and hope to establish the women from Ramsar Palawala as permanent partners in our small batch production process.

We are currently building a roadmap for a five-year association with PANS, during which we hope to eventually include 240 women in the fold and develop the scope of the project to include a second tier of advanced training on photography, marketing, inventory management and developing market linkages. Like all processes that are focused on nurturing holistic, enduring and people-centric systems, this project will grow slowly in its scale and impact, with learnings for us that we hope to carry forward in -similar projects across the country.

LESSONS IN NATURAL RED

24.06.2022

Natural Dyes / Ancient Knowledge Systems / Documenting Crafts

The colour red figures heavily in Indian crafts because of its symbolic associations with vitality, auspiciousness, divine feminine energy and love.

Through researching this vibrant, evocative colour, we will start to build shades of red into our next Nila collection, slowly developed over the course of a year.

Creating one-off swatches with local materials at Nila House gave us a sense of the range, but to grasp the full potential of what could be achieved along with overcoming the challenges of working to scale, we visited our mentor in Bagru, the natural dye master Seduram Chippa.

We were particularly keen to learn about locally-found, plant-based dye options. Whilst lac is one of the oldest known sources for red, it is not indigenous to Rajasthan – found more commonly in eastern India, particularly Assam – and the extraction process involves crushing the female lac insect along with her eggs and larvae to extract the shellac resin. With this in view, working with locally abundant plant-based extract sources seemed like the more sustainable, non-violent option. And as we discovered through our intensive extraction and dye sessions, these ingredients also have the potential to give a broad range of hues on the red colour wheel.

With Seduram ji guiding us, we worked on extraction and dye processes using the root of Indian madder (manjishtha) and sappan wood, which has an excellent medicinal bark with antibacterial properties, extensively documented in Ayurveda. We used the traditional ‘telkhar’ scouring method, using a solution made from the locally available salt ‘khar’ mixed with castor oil and cow dung to cleanse the fabric of impurities. For mordants, we used alum and the traditional earth-based gheru, which helped us achieve darker hues.

Our aim was to achieve a cherry red hue that would form the core identity of our future collection and perhaps more importantly, help us share a strong counter to the omnipresence of synthetic alizerin when it comes to red dyes. To underscore just how prevalent synthetic alizerin is, Seduram ji shared that had he not received a request for red dye without alizerin in years – the addition of the synthetic pigment was assumed to be a given. We were the first request for information on natural, plant-based red dye in a very long time!

Working with different combinations of dye stuffs and natural mordants we were able to achieve a wide variety of hues within the red family, ranging from a russet apricot to a brilliant rhododendron crimson. We are yet to reach the cherry red we had envisioned, but venturing deep into the extraction processes of plant-based natural red has certainly given us a sense of the vast knowledge system around just one colour. We will keep this space updated going forward.

So much of process-driven work is about incorporating happy accidents. It is incorrect to go about the natural dye process with a very specific shade or goal in mind. Rather, we are learning to let the colours of the earth reveal themselves to us on different surfaces, remaining open to what may come. The design process at Nila is generally responsive and not prescriptive. Whether we are working with artisans and their own aesthetic narratives or with natural materials that also have their own innate character, we remain open to variations, deviations, « accidents » and inconsistencies, for this is what sets apart a crafted object from a mass-produced replica.

SYAHI

MAKING THE COLOUR BLACK WITH ANCIENT NATURAL DYE WISDOM

1.06.2022

Natural Dyes / Ancient Knowledge Systems / Documenting Crafts

Syahi begar is the black and red printed textile from Bagru, part of the repertoire of print techniques that are grouped under the shorthand ‘Bagru prints’. For natural dyers, syahi begar is particularly interesting because of its use of the natural black ‘syahi’ dye.

Syahi translates to mean ‘ink’ and the dye is indeed a rich, inky black extracted through a slow reaction when iron ore and jaggery are combined. The black dye is an important element in natural printing traditions as well as developing the darker hues within the colour spectrum of certain natural dyes. In Rajasthan, Syahi is traditionally extracted from the iron ore of discarded and rusted horseshoes, which we might conjecture, is connected to the region’s history of martial clans.

The syahi has a particularly long extraction time, which is between three weeks to a month. We had the opportunity of learning about the history and extraction process of this important base dye from master dyer Seduram Chippa in Bagru. Over the course of several weeks, Seduram ji guided us through every step of this time-consuming but immensely rewarding dye process.

The process begins with treating the rusted horseshoes (or iron scraps) to a high heat. This is traditionally done on an outdoor fire made from dung cakes and wood. The metal scraps are left on the open flame till they have a fiery red glow, then removed and set aside to cool overnight. The next day, the scrap iron is soaked in water with jaggery (gur) and set aside to ferment for 3-4 days. The scrap iron is then taken out and the rust is rubbed off with sand and water. The scrap iron fragments are once again added to the jaggery and water mix and set aside to soak for 15-20 days. An experienced dyer will know when the syahi paste is ready for extraction by the tangy smell of the dye bath.

Syahi when mixed with madder or alizarin gives the red pigment that is used for the red-on-black Syahi Begar print. Syahi is also added to natural indigo to make it darker. In Bagru, when dyeing with this inky black dye, petals of the indigenous flower ‘Dawadi ka Phool’ are used to help the dye catch evenly through the fabric.

The process of making syahi is another example of traditional knowledge that is so deeply connected to the local history and ecology of a place and community. The process does require time, but it is rooted in values of reuse and minimal waste, leaving no harmful residue trail.

DOCUMENTING NATURAL DYES IN BAGRU – A STORY OF RESILIENCE AND RESURGENCE

26.05.2022

For centuries, natural dyes have been at the heart of India’s textile crafts. In Rajasthan, this knowledge is carried on through the Chippa community of Bagru, who have a long history of working with natural dyes.

In recent decades, the rich practices around natural dyes have dwindled, becoming something of a vanishing craft. The pressure to keep low prices for large-scale orders along with short timelines has forced printers and dyers to move towards toxic chemical pigments that have terrible long-term effects on the health of the land, water and consequently, the community.

Despite these changes in the use of material resources, there are some printers who continue work with natural dyes.

Over the last two years, we have been working to create a deep documentation of this precious and increasingly rare knowledge. Fortuitously, we were introduced to Seduram Chippa, who is over 80 years old and remains one of the few remaining guardians of knowledge on working with a vast repertoire of natural dyes from start to finish.

SEDURAM CHIPPA’S NATURAL DYE ENCYCLOPEDIA

While speaking to Seduram ji, we discovered that he has a working knowledge of extracting and dyeing with over 80 natural dyes, meticulously documented in notebooks over the years and alive like muscle memory. When we met him, Seduram ji had been working with natural dyes and printing techniques like Mendh and Gavarfali Dabu resist for over five decades. He is now happier to take on the role of a teacher, sharing his experiences instead of working as an active dyer-printer at this stage.

As a sign of the times, the younger generation, including Seduram ji’s grandchildren, do not carry the technical knowledge of preparing and working with natural dye baths. Through this documentation project, we hoped to archive the precious knowledge of Bagru’s natural dyeing traditions and celebrate Seduram ji’s life and work as a master artisan.

JOURNEY THROUGH NATURAL DYES WITH SEDURAM CHIPPA

Over the course of a year, we worked intensively with Seduram ji, learning and documenting his natural dye recipes by making each dye bath from scratch. We covered a total of 20 ingredients, detailed at the end of this article.

From the pre-dye treatment of the fabric to the dye bath and finishing – each step of the dye process revealed a sense of common-sense efficiency and resourcefulness that is so deeply rooted in traditional knowledge systems and guides the regenerative, sustainable essence.

For example, for the pre-dye step of scouring, the cotton fabric was treated to the method of ‘telkhar’. ‘Tel’, which means oil, and ‘khar’, which is locally available alkali found around water bodies. Seduram ji recalled a time when the river ran through Bagru and the khar could be extracted right by the river-bed. The river has long dried up, so the nearest source for khar was a lake, about 10 km outside the village.

We set out early morning to collect the khar which was then mixed with oil, water and cow dung to make a scouring solution. The pre-washed fabric was soaked in the telkhar solution, then removed, wrung out and set to rest overnight. The emulsion, we discovered, had naturally softened the fabric removing impurities and making it highly absorbent.

To ensure colour-fastness – that is, to ensure the colour fixes on to the fabric - we followed the traditional process of mordanting, using ‘Harda’ (myrobalan) and alum. Along with helping the dye seep into the fabric, mordants also give a range of colours from a single dye ingredient.

Week upon week, Seduram ji guided us through the process of creating dye baths with flowers, leaves, tree barks, kitchen scraps and the highly specialised ‘syahi’ extracted from iron scraps. In small-batch experiments with untreated fabric, fabric mordanted with harda and alum as well as a combination of both, we worked our way through 20 ingredients, giving a total of 80 shades. We have shared four recipes at the end of this article.

The valuable experience of learning from a master artisan-teacher like Seduram Chippa has given us a sense of the fragile, vanishing nature of age-old knowledge systems but also their resilience and timeless relevance because of the values and connection to nature that ground them. With thoughtful documentation and encouragement, traditional, regenerative craft systems have a chance to thrive, creating the promise of a gentler, sustainable future.

LIST OF DYE BATHS

Flowers: Marigold, Night Jasmine (Harshringar), Flame of the Forest (Palaash), Safflower

Barks/Roots/Heartwood: Indian Mulberry, Red Sandalwood, Sappanwood, Indian Madder

Dyers Alkanet, Gum Arabic, Jujube, Catechu

Kitchen ingredients: Pomegranate and onion skins, tea leaves, turmeric, saffron

Leaves: Neem, Henna

Metal extract: Syahi

DYE-BATH RECIPIES

You will need: Double-flame stove top; kitchen weighing scale; 2 vessels of 1.5l capacity; 1 vessel of 4l capacity; access to running water; dye ingredients

Harshringar / Night Jasmine

Take 100 g of dried harshringar flowers and separate into 4 batches of approximately 30gm each

Add 30gm of dried flowers into 1.5l water and boil for 20-30 minutes till it reduces and releases colour

In another vessel, take 4l of water and set it on high flame to make the dye bath

Strain the boiled, reduced liquid from the flowers into the dye bath

Add 500ml water in a fresh vessel with the next batch of dried flowers and set to boil

Dip the fabric in the dye bath, stirring and moving the fabric evenly through the dye bath

Top up the bath with the second batch of dye extract

Soak the fabric in the dye bath for 15-30 minutes on a low flame, until it starts to boil again

Once the dye bath reached a rolling boil, take out the fabric, wring and dry in shade

Neem leaves

Take 400gm of neem leaves and boil these in water for 20-30 minutes, until the colour releases

On another flame, make a dye bath by boiling 2l of water

Once the water has boiled, strain the extract from the neem leaves and add to the dye bath

Dip the fabric in the bath and let it soak

Keep stirring the cloth in the bath to ensure the colour catches evenly

Once the dye bath has come to a rolling boil, remove the fabric, wring it and leave it to dry in shade

Turmeric

For dyeing with turmeric, begin with boiling 750gm of dried pomegranate skins in water, then leave the skins to soak overnight

The next day, drain the pomegranate residue, collecting the water

Mix 150gm of turmeric powder in the pomegranate solution, mixing thoroughly so the turmeric dissolves completely without lumps

Dip the fabric in the dye bath, swirling the fabric evenly through the dye

Leave the fabric in the bath for 10-15 minutes, then remove it, wring and leave to dry in the shade

Sappanwood (Indian Redwood)

Take 100gm of dried sappanwood bark and separate into 4 batches, of approximately 30gm each

Add 30gm of the bark into 1.5l of water and boil for 20-30 minutes, till it reduces and releases colour

In another vessel, take 4l of water and set it on high flame to create the dye bath

Strain the boiled and reduced liquid from the first vessel into the dye bath

Add 500 ml water into a fresh vessel with the next batch of sappanwood bark and put it to boil

Dip the fabric in the dye bath, swirling the fabric evenly through the dye

Top up the bath with the second batch of dye extract

Soak the fabric in the dye bath for 15-30 minutes, on a low flame until it starts to boil again

Once the dye bath reached a rolling boil, take out the fabric, wring and dry in shade

MORDANTING

With Harda (Myrobalan)

For 1m of plain cotton fabric, use a ratio of 62gm of harda powder in 125ml of water. Mix the powder in until it dissolves completely. Dip the fabric in the solution, leaving it completely immersed for 15 minutes. Take the fabric out of the solution, wring it well and dry in the sun. Once dry, give the fabric a final rinse.

With Alum

For 1m of plain cotton fabric, take 50-75 gm of alum and dissolve it in 1.5 litre of water. To expedite the dissolving process, heat the solution on a stove top. Soak the fabric in the alum solution for 10 minutes. Wring it out and dry in the sun.

With Harda and Alum

To treat 1m of plain cotton fabric with harda and alum, take 62gm of harda powder and dissolve it in 125ml of water. Once the powder has dissolved, dip the fabric in the solution. Leave it to soak for 15 minutes. Take out the fabric from the solution, wring well and dry in the sun. Now dissolve 20-25gm of alum in 1.5 l of water, heating the solution on a stove top to expedite the process. Soak the fabric in the alum solution for 10 minutes. Wring it out and dry in the sun.

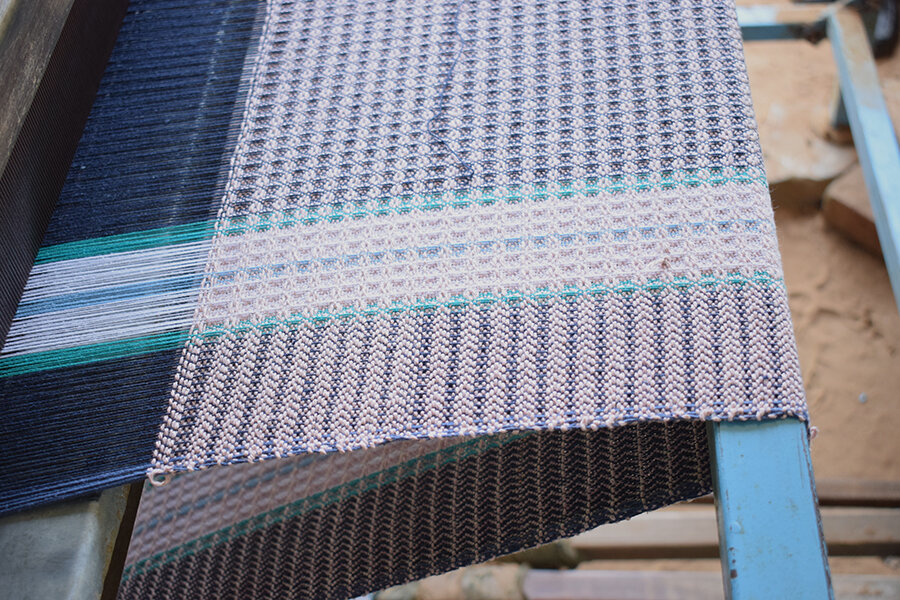

KANDU: A COTTON REVIVAL STORY FROM NORTHERN KARNATAKA

11.05.2022

Cotton cultivation has been at the heart of textile stories for thousands of years which tells us that is the system and not the crop itself that lies at the heart of a conversation around the sustainability of cotton. In India, cotton cultivation pushing GMO seeds has failed small-scale farming communities and destroyed the land, fracturing once vibrant, local and circular textile systems.

With this in view, Nila has been seeking out partners to support sustainable cotton farming practices and our journey connected us to Kandu in Karnataka. Our recent travels across southern India was a wonderful opportunity to visit the Kandu team in Melkote, and get a fine-grain sense of the depth of this initiative. Their work with reviving northern Karnataka’s indigenous brown cotton is an uplifting example of how true and inclusive sustainability can be created through cotton cultivation.

Their story begins with Chennabasappa Masuti, a farmer who began cultivating a hybrid cotton strain that had been developed at the local Dharwad University. This strain produces a medium staple cotton crop that was well suited to spinning and weaving. Resilient and rain-fed, this hybrid indigenous cotton requires no chemical pesticides or fertilisers, making it truly organic.

Kandu came into being in 2018, inspired by Chennabasappa’s intrepid experiment and a sense of the potential of this natural, organic brown cotton. Working under the trust ‘Udaanta’ (which means ‘for example’ in Kanada), Kandu operates as a collective of experts and facilitators, building what they call ‘land to loom’ networks in the region. The collective of farmers working on this revival project has grown to 5 small-scale farmers, including 2 women.

Chennabasappa Masuti | Image courtesy Kandu

Through its small-scale but impactful cotton revival initiative, Kandu has benefitted farming communities and has energised the textile chain in the area, bringing in ginners, spinners and weavers. The brown cotton is spun on ambar charkhas, with the strong brown yarn set to looms at the Janapada Seva Trust, a KVIC-recognized institution that produces high quality handspun, handwoven khadi.

Kandu’s natural brown cotton yarns and textiles are currently available to buy through their website kandu.in.

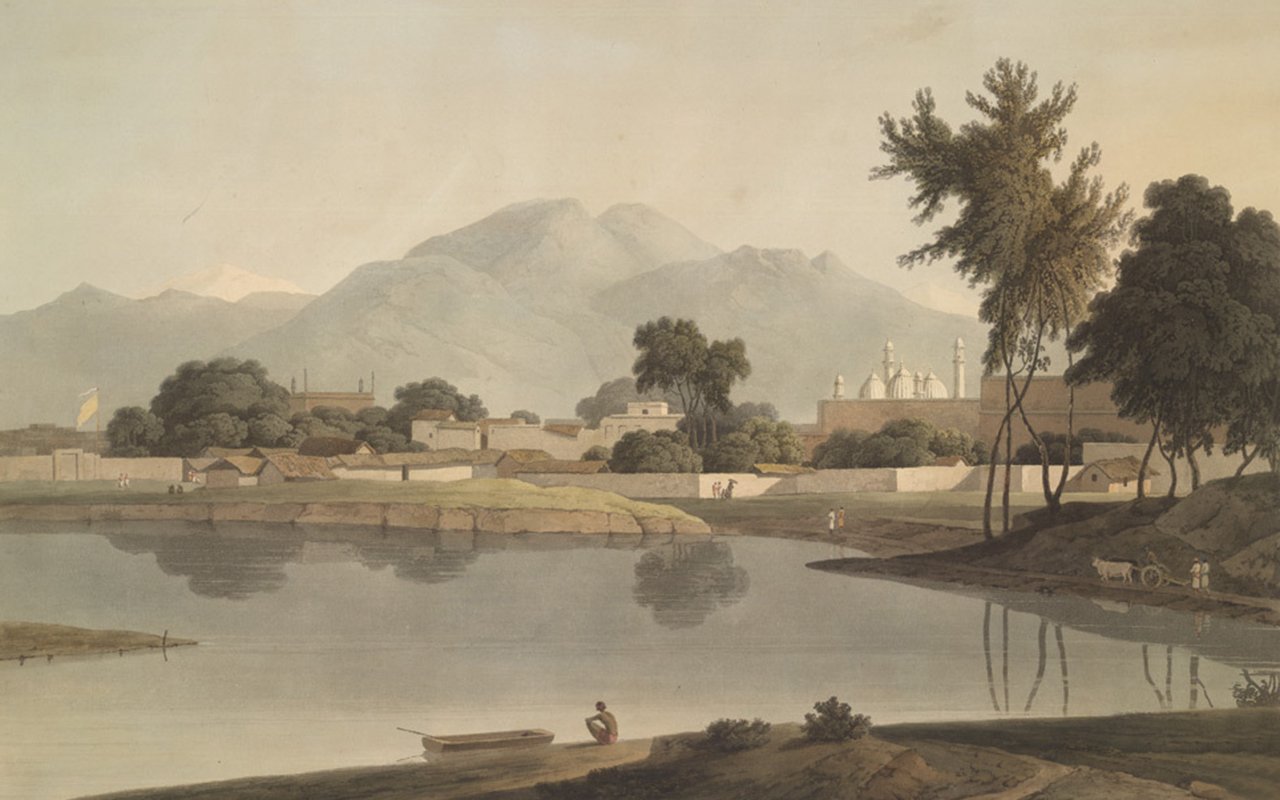

RAFOOGARI: THE ART OF INVISIBLE MENDING WITH INTEKHAB AHMAD FROM NAJIBABAD, UTTAR PRADESH

25.01.2022

Exhibition catalogue

The city of Najibabad in the north-western state of Uttar Pradesh is one of the last bastions of rafoogari – a highly specialised needlework craft involving the repair and restoration of priceless textiles through invisible mending by hand. Najibabad’s special connection to rafoogari goes back its roots as a city founded in the 18th century with the intention of facilitating and benefitting from the thriving commerce of Kashmir. The prolific shawl industry of Kashmir and the range of craft economies it supported thus found a home in Najibabad, under the patronage of its nobility, during the ebb of the Mughal empire.

The art of rafoogari is a sophisticated undertaking, both as a technique and as a philosophy of preservation and creative repurposing. Like many historic craft systems, rafoogari skills are passed down through generations in a system of apprenticeship. Today, the existence of this specialist craft rests with a small group of artisans with a serious concern that it may face into oblivion without the right support and economic future to draw the next generation into the fold.

Intekhab Ahmad is a fourth-generation rafoogar and a vocal advocate of its preservation and revival. Intekhab works with a team of master rafoogars and younger rafoogars-in-training, preserving and repurposing valuable pashmina, jamavar and kani textiles through impeccably executed rafoogari darning techniques. Some of the textiles that come through his workshop date back as far as 18th century, with provenances connected to the Mughal period.

To maintain the economic viability of the craft is a balancing act and Intekhab is aware that the relying solely on textiles and craft practices of the past is not enough.

In a recent conversation with Anuradha Singh (Director, Nila) Intekhab shared - “The tastes, fashions and requirements of the modern world have changed. Younger customers are not attracted to the heavy work and generous width of traditional Jamavar shawls. They need lighter, less ornate pashminas that can we worn as scarves or lighter shawls. We recognize this and try to adapt to this demand.”

Whilst Intekhab works exclusively on rafoogari pieces – intricate and expertly strategised restorative darning – his workshop employs embroiderers, often women, who craft intricately hand-embroidered textiles based on updated designs by Intekhab. The precise embroidery stitches to be used for each ‘munavar’ or border design, along with the colours and motifs are guided by Intekhab’s expertise and brought to life by the artisans affiliated with his workshop. The mentorship of master artisans like Intekhab provides important skill-building, a chance for meaningful work and a sense of pride and connection to historic roots.

When asked by Anuradha on his thoughts for rafoogari’s future, Intekhab said - “My wish is that the art of rafoogari does not fade away. Forums like workshops and exhibitions in cities are an opportunity for us to share the value of this craft with an interested audience that can support our work.”

Through January 2022, Nila House had the honour of hosting an exhibition-sale of hand-embroidered and restored antique textiles from the Najibabad workshop of Intekhab Ahmad. It was a privilege to be able to share the history and technical brilliance of rafoogari through Intekhab’s work.

The exhibition catalogue is available to enjoy (linked at the top of this article) and a select number of pieces are still available to order. Intekhab Ahmad is also welcoming custom orders, which we will be happy to facilitate with no charge.

Write to us at info@nilajaipur.com with “Order request for Intekhab Ahmad” as the subject line or contact him directly.

Intekhab Ahmad | Contact Number: +91 98116 49326 | Instagram: @intekhab.ahmad.902

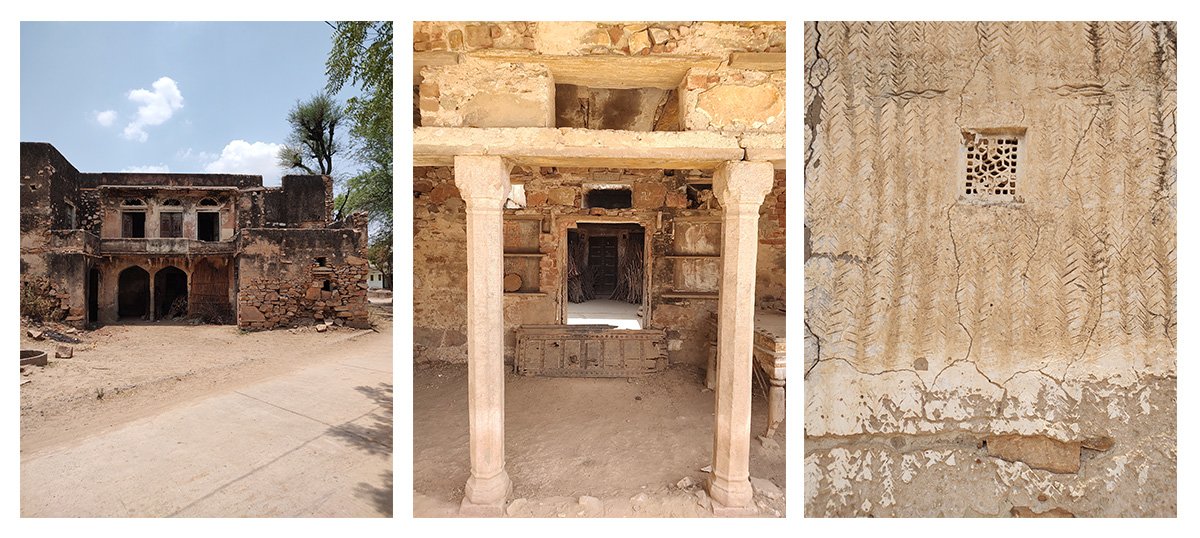

GOVINDGARH WEAVING INITIATIVE

05.10.2021

Some days feel more auspicious than others to begin a project that has been bubbling away as an idea. Serendipity or just coincidence, on 7 August, National Handloom Day, we set off with our design-innovation weaving project in Govindgarh. Marked annually as an homage to Mahatma Gandhi’s Swadeshi Movement, the spirit of Handloom Day felt resonant with the idea of the weaving project – reviving, supporting and uplifting handwoven textiles at the very grassroots.

After a month of laborious work cleaning and restoring a weaving unit that had been in disuse and damaged by the monsoon rains, the looms were ready. With a cheerful puja for blessings and luck, the weaving unit was open for the project to take its first steps.

RESULTS FROM THE FIRST MONTH

Over the course of the first month, with two sample looms working simultaneously, our team of collaborating weavers managed to create 25 sample weaves, each meticulously documented so that we can eventually build a library of innovative weave designs that could be used as a valuable resource by the weavers of Govindgarh.

Following an agile, light-touch approach, the unit is working on design developments by innovating directly on the loom, using excess yarn, natural fibres like jute and off-cut textile pieces from the Nila studio. The results have been quite extraordinary, with thoughtful conceptual weaves emerging from the process, building on the weave repertoire of these already highly skilled weavers.

BUILDING THE VALUE CHAIN

As a way to support a farm-to-fabric value chain that is gentle on the earth, we also worked with our weaving partners to set up a 60 litre tamarind vat that will encourage dyeing experiments with natural indigo. Our Nila team, now experienced with setting up and tending to several healthy vats of various capacities, helped set up the Govindgarh vat with an immersive, interactive workshop.

As the Govindgarh weaving project grows, the hope is to create a strong model for skill building and design development that will be a valuable resource for us to share with other partners across India. We will continue weekly updates from Govindgarh on our Instagram feed under the tag #LiveFromTheLoom.

THE FIRST INDIGO HARVEST - PURE BLUE GOLD

17.07.2021

On the 27th of March, on a sunny morning in the afterglow of Holi, we planted our second batch of indigo seeds on the Nila terrace garden. Having a plot of earth to grow a precious crop of indigo had been a dream since the idea of Nila was first seeded. After the gray pall of Covid and lockdowns, the act of planting indigo seeds was a gesture that filled us up with renewed hope.

As the trials of the Covid second wave ballooned by April, Jaipur like the rest of India, went into lockdown again, with the team working remotely. At this time, our wonderful on-campus security team took on the task of tending to our indigo farm, sharing daily updates that kept up our spirits through the difficult days. They also picked up the skills of maintaining our 100 litre sour vat, with expert remote guidance from our team.

In late June, as the team began to return to Nila House, the sight of a flourishing indigo crop brought much joy. It was almost time for harvest. Last week, in keeping with health protocols, core members of the Nila team, joined by our security team (now indigo team), harvested two varieties of Indigofera Tinctoria, soaking the leaves for fermentation and eventually managed to extract indigo paste – thrilled voices called it “pure gold!”.

Here is a detailed account of Nila’s first indigo harvest and extraction – from seed to dye.

SEEDING THE NILA INDIGO TERRACE FARM

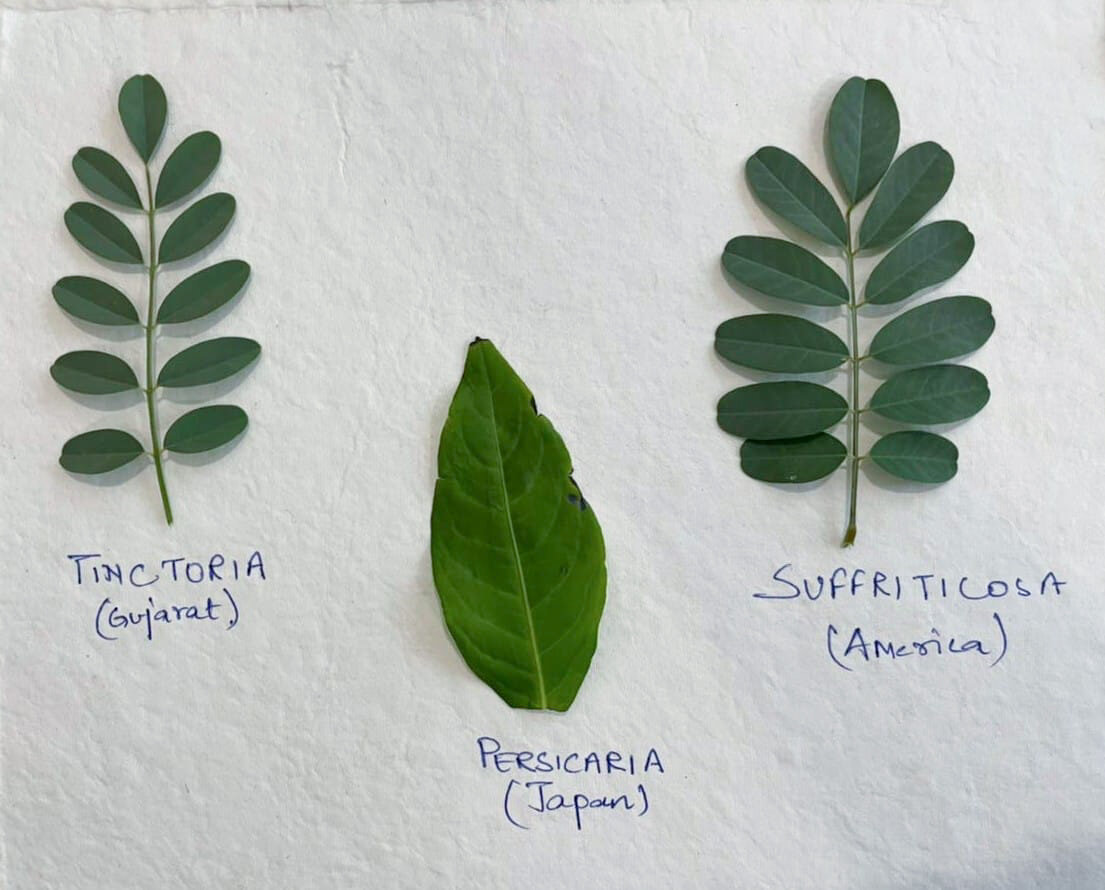

We planted four kinds of indigo – two varieties of Indigofera tinctoria from Gujarat and Rajasthan, one batch of the Japanese Persicaria tinctoria and one batch of Suffriticosa tinctoria. We were lucky to receive the Persicaria and Suffriticosa seeds from our friend and renowned indigo expert, Linda LaBelle. The Gujarat variety of Indigofera tinctoria came from Siju Ashok, a young indigo master with an inspirational love and commitment for natural dyes.

Following a night of a pre-soaking to help the germination process, the seeds were set into the troughs on our terrace, prepared in a nourishing combination of fresh soil, peat and cow dung. Watered diligently, the seeds began to show signs of sprouting in a few days. If it took well, the crop was estimated to grow to its harvest-ready height in 90 days.

LOOKING AFTER THE INDIGO TERRACE FARM

It was a challenge to look after the health of the indigo saplings through the harsh summer months, particularly when the usual team was unable to reach Nila House. But the magical endurance of indigo, combined with the instinctive and attentive care from the on-ground security team tided us through the difficult months. Regular de-weeding was important to ensure the saplings we not over-run by wild grass and weeds.

THREE MONTHS ON – HARVEST TIME

Three months whistled past and as we began to gradually return to Nila House post-lockdown, we came back to healthy indigo crops averaging a height of 5 ft - ready for harvest. On 5 July, at 10 am, 101 days after the seeds were sown, we harvested our first indigo crop of the year from the Nila terrace farm.

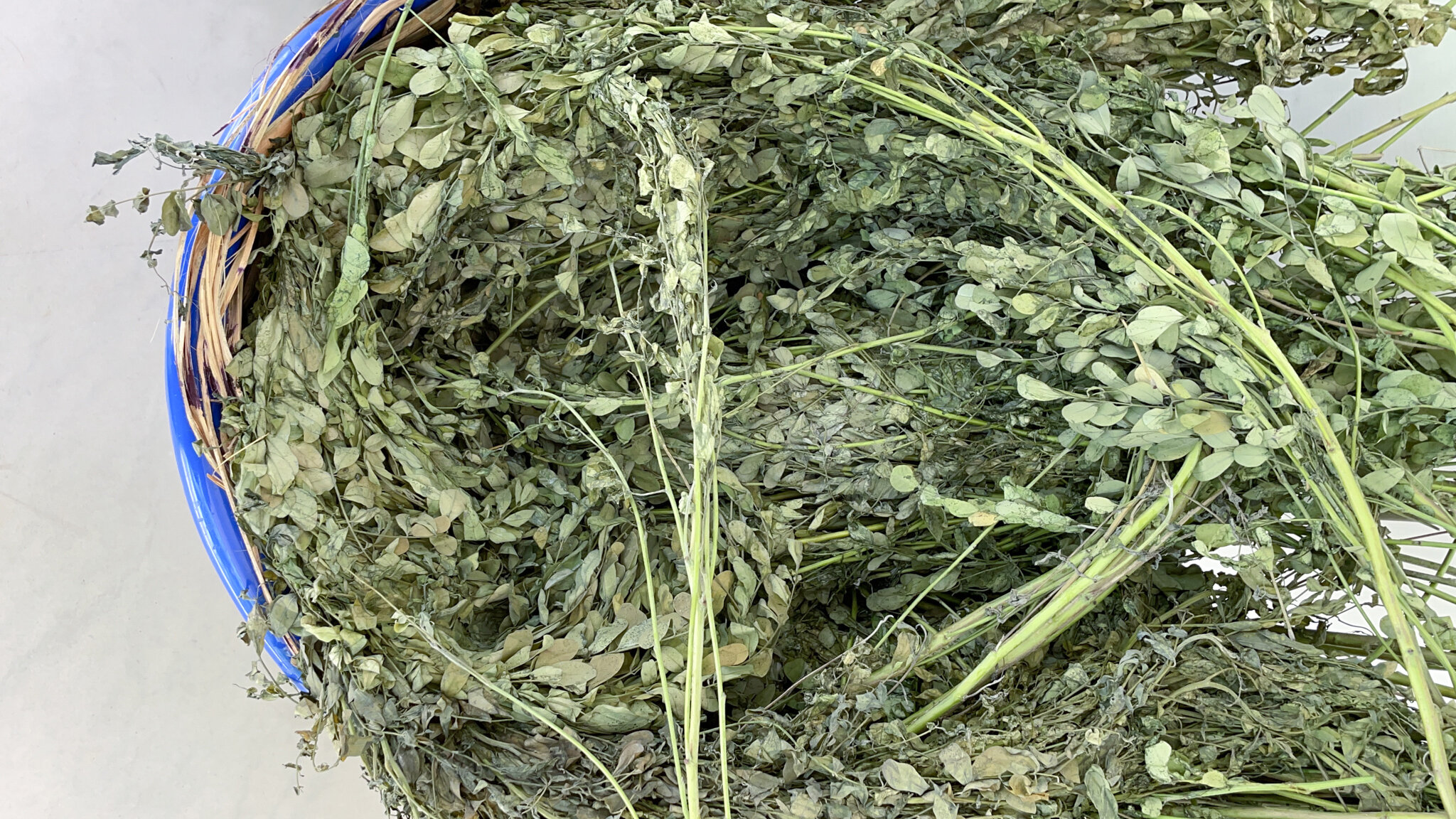

We successfully harvested both varieties of the Indigofera Tinctoria, making sure we cut 6 – 7 inches above the base, to keep room for new shoots that seemed to be already coming up. These, we hope, will make out second harvest.

SOAKING THE INDIGO CROP – THE EXTRACTION PROCESS BEGINS

The indigo crops were bundled according to size, to be plunged in tubs of water to begin the soaking and fermentation process. It was crucial to add them in within a 2 hour window or else they would start to dry up (bigger crops are usually harvested and soaked early morning, to skip the mid-day heat).

Following expert advice from Kiran Sandhu and Kanika Mukherjee of Utsaworkshop, we sourced 200 litre, durable plastic drums for the soaking and fermentation process. Stone weights were set aside to press down on the indigo leaves to coax the extraction process. The bigger bundles were placed at the bottom of the empty tub, followed by the smaller batch. The stone weights were carefully placed on the bundle pile, ensuring the weight was evenly distributed.

The tub was then filled with regular water, up to 6 inches above the height of the indigo bundle, ensuring they were completely immersed. We tested the pH of the water to be at a fairly neutral reading of 8.4. The tubs were covered lightly with lids and the indigo bundles were left to soak for the next 24 hours.

DAY 2 of EXTRACTION PROCESS – OXIDISATION

Next morning, the indigo leaves that were left to ferment overnight, were gently taken out. The nitrogen-rich plant waste was set aside and would be used as nutritious fertilizer for the next crop. We made sure to use a strainer to sieve out the excess liquid instead of squeezing or pressing down on the plant mass.

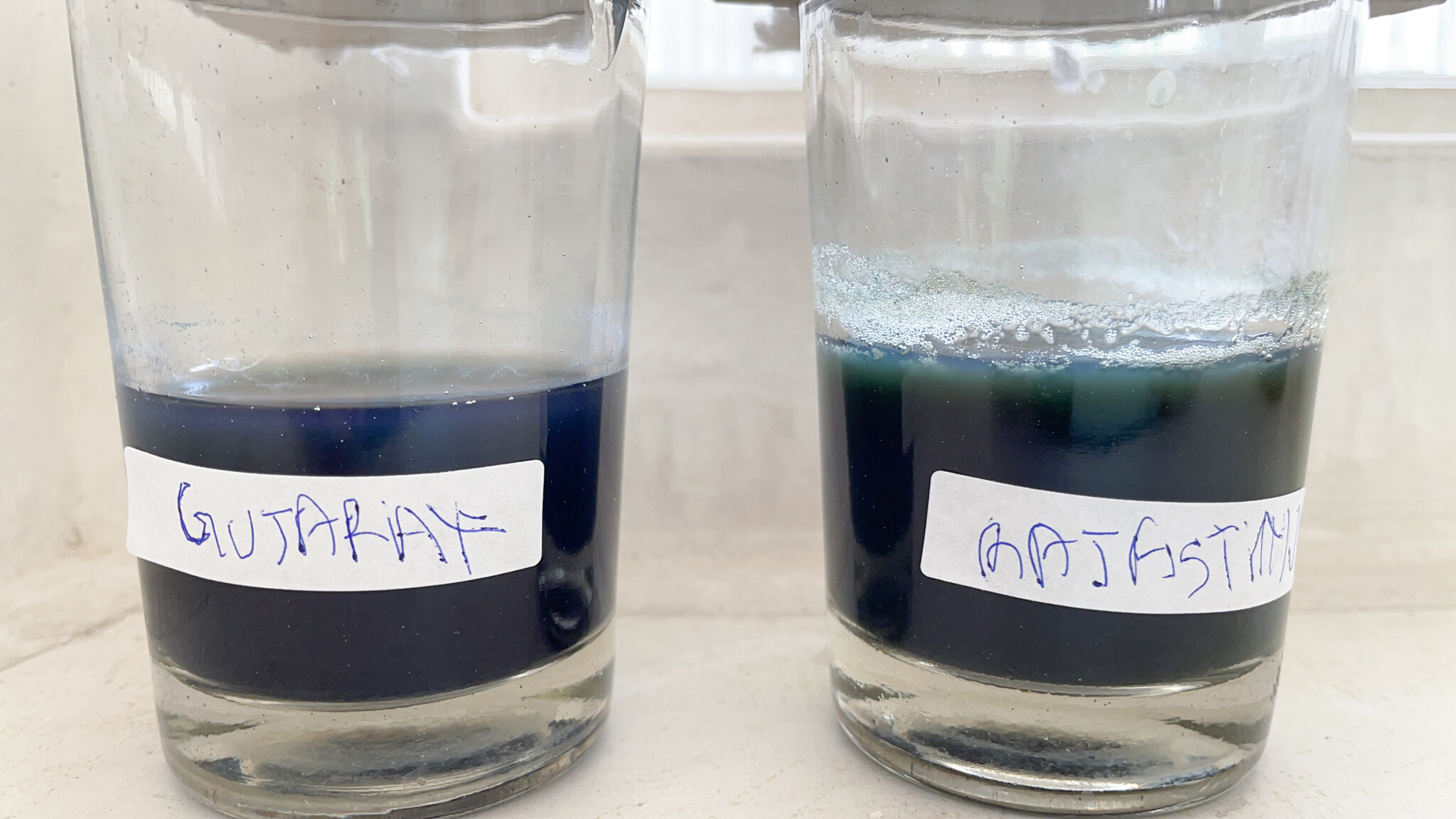

Traces of colour could be seen in the liquid left behind – a fresh, green liquid with an iridescent film of purple-blue froth lightly sitting on the top. The liquid was now ready for the next step of oxidization.

A lime water mix, with the lime (Ca (OH)2) added in proportion of 1% of the weight of the total crop was prepared and added to the vat, changing the pH to 10.2. To aid the oxidization process, the liquid would need to be whisked, for which we used a cane basket that allowed the liquid to seep through and breathe perfectly. The whisking process required an energetic, rapid in-out gesture, pulling the liquid in beautiful, long streams with every movement so the liquid would come in contact with air. The entire process took 2 hours, with the team taking turns to whisk.

The lemon green indigo water turned to a bright blue-green with the oxidization and the light bubbles turned frothier, like sea foam. A teaspoon full of indigo liquid was collected periodically to gauge the progress. Once we were able to see particles of colour in the liquid it was time to stop whisking. The tub was once again set aside for 24 hours, to allow the indigo to settle.

DAY 3 of EXTRACTION PROCESS – DISTILLATION

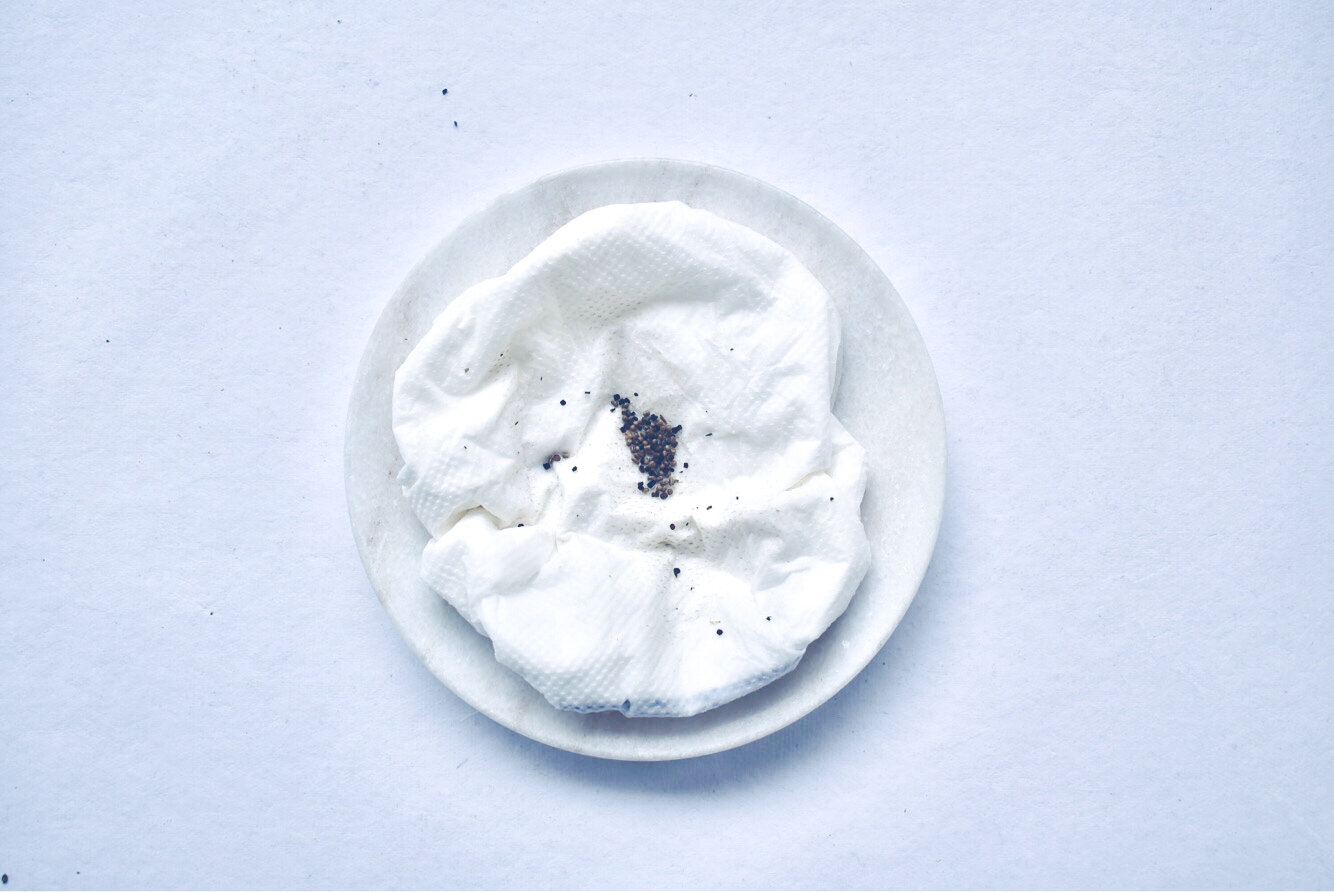

After the 24-hour rest period, the indigo had sedimented to the bottom of the tub, with a liquid fully oxidized. We placed a muslin cloth on the mouth of a second tub. Without agitating the liquid in the first drum too much, we began pouring out the indigo liquid from tub 1 to tub 2, with the muslin cloth acting as a slow sieve. Once we reached the bottom of tub 1, the liquid seemed denser, this was gently poured out, leaving behind a rich residue on the cloth.

DAY 4

The liquid was allowed to seep through gradually, a slow process over several hours, without any additional force to expedite the process. Once the liquid had completely seeped through the muslin cloth, what was left behind was a rich paste of the deepest indigo – we had our ‘blue gold’, ready to be gently scrapped off and collected.

Our paste of pure indigo needed to be stored carefully. Unlike indigo powder or blocks, indigo paste is vulnerable to mould and needs to be stored in an air tight container, refrigerated or used immediately in a live vat.

THE OUTCOME

Total Crop Yield : 17.66 kg of Indigofera Tinctoria ( 8.28 kg from the Rajasthan seeds and 9.38 kg from the Gujarat seeds)

Indigo Extracted: 1.72 kg or 10.26% of indigo per kilo of crop (0.94 kg from the Rajasthan crop 0.94 kg and 0.78 kg from the Gujarat crop)

The indigo crop from the Rajasthan Indigofera Tinctoria seeds gave a green-blue paste while the Gujarat crop gave a deep, dark indigo paste, reminding us of the subtly unique characters of varieties of the same indigo strain.

INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S DAY 2021: CELEBRATING THE RESILIENCE & ENTREPRENEURSHIP OF WOMEN

08.03.2021

international women’s day / women artisans / entrepreneurship / women

In the early days of Nila, as we talked about what our ethos and remit of work would be, we were quite clear at the outset that economic empowerment of women through craft would be an important area of work for us.

The conversation on what defines a “woman’s work” has taken on a special importance through last year, when women found themselves once again shouldering multiple responsibilities compounded by the extraordinary circumstances of lockdowns and the pandemic. In communities where women’s health and well-being are often treated secondary, it has been inspiring to see communities of women come together and take the lead, as women inevitably do.

Nila is happy to have been able to reach out and provide the support in terms of a consistent flow of meaningful work and exploring creative avenues of skill development, despite the restrictions. The solutions have been simple but impactful, creating a ripple effect that we hope will leave a lasting, positive imprint on economic empowerment of the women in these communities.

GOVINDGARH SPINNING INITIATIVE

Early on in the nation-wide lockdown, we realised that artisans such as spinners, working down the value-chain would be particularly affected and would need support. Govindgarh, a small town close to Jaipur, felt like a good starting point as it was relatively accessible and had a history of spinning women. The women in Govindgarh had been cotton spinners for generations, though many had stopped for the last decade or so, often opting to work on local public works projects under the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) because that offered a steady income, even if it was at minimum wage. Those who continued to spin for the government-supported Khadi enterprise, were spinning a coarser yarn. With the lockdown, however, work on both fronts slowed down or stopped entirely, drying up precious sources of income.

When Nila began working in Govindgarh, we discovered that the women had already been set up into Self Help Groups (SHGs). This was an important and useful foundation. Nila began working with the community of women spinners to get skill-building sessions in place, at first via virtual communication and later through smaller, in-person workshops. We discovered that several of the older women still had expert skill with the Bardoli charkha and were capable of spinning a finer yarn of 10 and 12 count. The training sessions also encouraged the younger women to take up spinning, many of whom had no prior experience but were keen to learn. Furthermore, Nila arranged for cotton slivers to reach the spinners so they could spin from their homes. Whilst the logistics of this were challenging, we ended up getting 42 kilos of yarn at the end of three months, for which the women were paid.

By assuring the women that there is a demand for their hand spun yarn, Nila has been able to encourage more women to join the spinning initiative to both preserve the skill and carry it on to the next generation as well as upskill to create better opportunities. We now work with women across the ages of 23 – 64, with younger women joining in, eager to take the lead on the project. Nila is working with them to help with training on documentation, management and entrepreneurship. The spinning initiative is an important step in Govindgarh, where several men in the community are already weavers and younger women are showing a keen interest to revive and build up the value chain to ensure income security in the long term.

NILA X ARKE

LBCT works with SHGs across Rajasthan, Maharashtra and Haryana. Members of these groups participate in production work form a community-developed women’s collective called ARKE. This collective carried out exceptional work during the difficult months of last year. Whilst LBCT mobilised to arrange for food supplies in villages during the critical early days of the lockdown, the women associated with ARKE began sewing face masks - a simple, yet highly impactful course of action to take care of their family and community’s health. The mask-sewing campaign was supported by LBCT and turned into a source of purpose and income for the women, particularly at a time of great economic distress. Over 100,000 masks were made and directly contributed to the incomes of these households whilst also controlling the spread of the virus in these communities.

Once the lockdown restrictions eased, Nila collaborated closely with ARKE and LBCT to develop skill-building sessions that have been in progress since October 2020, including a session on eco-printing at Nila House. The sessions which have run on the energy of the LBCT and ARKE SHGs, have given the women an opportunity to build on and pick up new skills - some as easy as eco-printing - which has encouraged creativity and a feeling of greater empowerment and security in the future.

Nila’s work with ARKE and LBCT has affirmed our belief in the importance of grassroots community collectives that can mobilise quickly and effectively as well as the value of skill-building for the long term.

UTSA, WEST BENGAL

Nila’s association with Utsa Workshop goes back to the early stages of our story. The dynamism of this small artisanal Kantha studio immediately resonated with us and Utsa joined us as collaborators, along with designer Simon Marks, on our Kantha pieces for the first Nila collection.

As the news of the nation-wide lockdown came to us in late March 2020, our thoughts were with our artisan sisters in Birbhum, West Bengal. We share Utsa’s story as there is much to learn from the experience of this small yet dynamic artisan studio.

Here is an excerpt from our recent conversation with Utsa, as we looked back on that time:

“Some years ago we presented our story at the Stockholm Resilience Centre. We thought of that experience during the lockdown, as we contemplated the meaning of resilience. Restrictions on movement meant we were not able to actually be physically present in order to work through sampling the designs and hand out the embroidery work to the women, who would usually come by our studio to collect this. We worked out a way to get the work dropped off safely to individual homes, which was a logistical challenge, though turned out to be not impossible. Since the women would typically work from home, we realized soon enough that there was zero disruption to getting any work completed. The younger women and girls, who may have been reluctant before, joined in as a productive way to spend time and chip in. New concepts and possibilities and ways of working emerged - some women shone bright as wonderful artists with the ability to design through the disruption while others rose to the occasion as logistics experts, whom we could rely on for dispatching and collection of work. We must acknowledge the role of the men in the community, who supported with enthusiasm and energy and helped keep the wheels turning.

The experience of working through the COVID lockdown reinforced our belief that interpersonal relationships and expectations are vital for studios like ours who follow slow-process production. We were fortunate to have clients who stood by their order commitments and understood the value of what we do as well as the challenges we were facing. The larger learning on sustainable models came from the villages. Whilst unable to visit the villages for months, we got constant reports of villages coming together to support the poorest in their communities with food and money; each village came up with a strict system of restricting movement from cities thereby controlling the spread of the virus. By and large, life carried on fairly peacefully. We put this down to the village ecosystem where people take responsibility for each other and act as one extended family. There’s a valuable lesson here on how to build resilient ecosystems.”

NEW BEGINNINGS

19.03.2020

indigofera suffruticosa / persicaria tinctoria / seeds / nurture

Indigo, nature's only source of blue dye, is obtained from plants in a process that is full of new learnings and surprises. While we have experimented with dyeing using natural indigo, we thought of taking a step closer to its roots and focusing on growing indigo at Nila House.

In March, when the winter was almost over, we thought to sow two different varieties of Indigo; tropical indigo (Indigofera suffruticosa), and Japanese indigo (Persicaria tinctoria). On Day 1, we soaked 50 seeds of each variety overnight in separate beakers with little water (useful tip – helps in faster germination) and covered the vessels with cotton.

On the morning of Day 2, we moved the seeds onto moist tissue paper to get some air before placing them in the soil trays. One of the master weavers, Vikram Valji from Kutch said in a video about how indigo is like a child, with a mind of its own. We have to give it what it needs, the right kind of soil, temperature, and water along with heaps of patience, attention, and care. This was challenging but we were fortunate to have Sridhar Lakshmanan, a farming expert, to help us in the next steps. We also dug up our notes from the various presentations and workshops that we had attended in the past.

Sridhar helped us prepare the soil with equal parts of Vermicompost, Cocopeat (improves soil aeration and enriches the soil with micro-organisms) and 4 hands full of Vermiculite (mineral to protect the seeds from damage). Some water was also added to make the mixture moist.

By the time our soil was ready, the sun was settling down and we began to place the seeds in the trays one by one with the utmost care. Again, after placing the seeds, we sprinkled a little bit of soil compost and water on top to allow it to settle through the night. We placed the trays in a corner to avoid direct sunlight (4 hours of sunlight is enough initially) and covered it with a wet jute sack (it helps in ensuring the roots are strong and there is good air circulation).

After day 2, we have been looking after the seeds on a daily basis by watering them, checking the temperature of the soil, adding vermiculite and cocopeat when necessary, and keeping them away from monkeys (yes, that happens in Jaipur).

It was a great learning experience to sow our own seeds of indigo to understand this magical dye in all its phases. A new beginning at Nila! We will keep updating our journal with more stories about the growth of our saplings. Until then, stay safe, stay indoors.

THE FIRST DIP

3.01.2020

natural dyes / indigo / dye-works / Bagru